The Good Life

In my last newsletter, I posed three questions that I believe we should ask ourselves throughout the course of our lives. In this issue, I am going to address the first of the three questions: What does it mean to live a good life?

Media and popular culture work hard to convince us that the answer to this question lies in the amount of money we have, the number of possessions we own, the relative quality of those possessions (the more luxurious, the better!), and the number of extravagant experiences we can accumulate. Examples abound. My Lottery Dream Home, Bahama Beachfront, and other house hunting shows (my latest television obsession) all portray people searching for the perfect home that will set them up with a “happy-ever-after” lifestyle. Commercials show people living satisfying lives after having purchased a given product. And Social Media Influencers make it their “job” to live fabulous lives by traveling to expensive resorts, wearing fancy clothes, and using luxury products—and then try to convince us to follow their lead and purchase the same.

It’s not a surprise. Our capitalist system relies on us buying into the notion that we should always be striving to accumulate more and better things. The problem is that such goals rarely lead to personal fulfillment. Actually, the system is designed in precisely these terms: if, in the end, we remain personally unsatisfied after our recent purchase, then the solution obviously must reside in our next purchase.

Similarly, we are conditioned to believe that advances in technology and industrial production have vastly improved the quality of our lives over time, but before we accept this belief wholesale, we must pause. If we are all spending one to two hours a day commuting back and forth to work to maintain this “improved” lifestyle, is that a good life? Studies of happiness have shown that there is a strong inverse relationship to the amount of time one commutes and one’s overall well-being. (One of the few positive outcomes from the current pandemic may be the realization that the hamster wheels we had been running on are not as desirable, or as necessary, as we once thought.)

In fact, before we settle in to the idea that our enjoyment of advanced civilization offsets the relative misery of our working lifestyle, consider the following. Small-scale tribal societies, who normally rank as “primitive” by our economic and technological standards, enjoyed much more leisure time, lower stress, and greater personal connections within their communities than we do. One study shows that a member of the Ju/’hoansi “Bushmen” tribe, who lived an isolated existence in Namibia and Botswana up until the late 20th century, spent a total of 17 hours per week searching for food and another 20 hours on chores, whereas average full-time employees in the U.S. now spend 44 hours per week on work before they even get to domestic chores and childcare. The Ju/’hoansi enjoyed far more time than we do to lounge, gossip, dance, sing, and tell stories. Their lifestyle sounds a lot like the one that my television house hunters are seeking!

The supposed superiority of our Western lifestyle takes another blow when we consider American colonial history, where we can easily find cases of individual European settlers deciding to abandon their settlements and live instead with Native people. On the other hand, the opposite—Native people freely deciding to abandon their tribe and live among Europeans—is extremely rare in the historical record. Westborough’s story of the abduction of the Rice Boys in 1704 offers one case in point, with Silas and Timothy Rice preferring to stay with the tribe that abducted them rather than return to Westborough with their father when he finally located them.

Other people may find answers to living the good life simply in accumulating wealth, which brings with it security and stability. I have to admit that there is a lot of appeal to this approach, because I really value security and stability. But then I came across the following passage while recently reading The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky:

[E]very one strives to keep his individuality as apart as possible, wishes to secure the greatest possible fullness of life for himself; but meantime all his efforts result not in attaining fullness of life but self-destruction, for instead of self-realization he ends by arriving at complete solitude. . . . He heaps up riches by himself and thinks, ‘How strong I am now and how secure,’ and in his madness he does not understand that the more he heaps up, the more he sinks into self-destructive impotence. For he is accustomed to rely upon himself alone and to cut himself off from the whole; he has trained himself not to believe in the help of others, in men and in humanity, and only trembles for fear he should lose his money and the privileges that he has won for himself. Everywhere in these days men have, in their mockery, ceased to understand that the true security is to be found in social solidarity rather than in isolated individual effort. (2.6.2 d)

Hm, I never thought of wealth in that way.

My central aim here is not to argue the (de)merits of capitalism and technological development. Nor do I want to imply that economic comfort should not be part of what it means to live a good life. I only raise the above examples because of the easy hold they seem to have on all of us and to show how the seemingly simple question that I ask may be far more complicated—yet personally fulfilling—to answer than we may first think.

For me, my answer to the question, “What does it mean to live a good life?” lies in being able to explore and experience to the best of my ability the full extent of what it means to be human, which leads to our next question. . .

Next up: How can we fully experience what it means to be human?

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

What do you think makes up a “good life”? Share your thoughts in the Comment section.

Suggested Reading

* * *

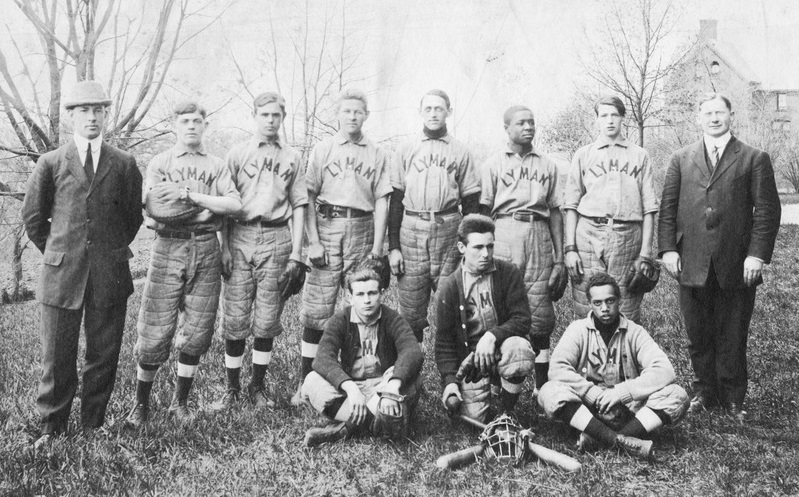

The arrival of spring brings the arrival of baseball! Stop by the display case outside of the Westborough Center and check out the new exhibit, Westborough Baseball, to see the game through the eyes of Westborough history.

* * *

Historical church records can shed tremendous light on the lives of everyday people living in 17th– and 18th-century colonial America, and no town knows that more than Westborough. New England’s Hidden Histories, a project of the Congregational Library and Archives and a crucial partner in the Westborough Center’s Ebenezer Parkman Project website, seeks to digitize these historical records and make them freely available to the public.

Learn more about this exciting digitization project in the YouTube video, New England’s Hidden Histories: A Roundtable Discussion. James (Jeff) Cooper, the director of the project, and his guests talk about the challenges of hunting down, collecting, capturing, and storing these fragile records in digital form. Who knew that dusty church records could be so interesting?!

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Local History Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox: https://www.westboroughcenter.org/subscribe-to-updates/.