March 2021

In March of 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Boston Clemente Course had to go online with its classes. For twenty years, the course has been held in-person at Codman Square Health Center in Dorchester. This disruption could have spelled disaster, but the students and faculty persevered.

Timothy Patrick McCarthy serves as the Stanley Paterson Professor of American History (he is also the Academic Director Emeritus) in the Boston Clemente Course in the Humanities, a free college course for lower income adults in Dorchester which was a co-recipient of the 2015 National Humanities Medal from President Barack Obama. Dr. McCarthy has taught the American History portion of the Boston Clemente Course since its founding in 2001. Mass Humanities operates the course in partnership with Codman Square Health Center and Bard College.

Dr. McCarthy is an award-winning historian, educator, and human rights and social justice activist who has taught at Harvard University since 1998. He currently holds a joint faculty appointment in the Graduate School of Education and the John F. Kennedy School of Government, where he is Core Faculty at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. The adopted only son and grandson of public school teachers and factory workers, Dr. McCarthy graduated with honors in history and literature from Harvard College and earned his M.A., M.Phil., and Ph.D. in history from Columbia University. A noted historian of politics and social movements, he is the author or editor of six books, including the forthcoming Reckoning with History: Unfinished Stories of American Freedom (Columbia UP) and Stonewall’s Children: Living Queer History in an Age of Liberation, Loss, and Love (New Press).

John Sieracki, Director of Development and Communications at Mass Humanities, interviewed Dr. McCarthy via Zoom.

John Sieracki: Tell me about the pandemic and going online. You must’ve had experience with online courses before.

Tim McCarthy: Never.

JS: So going online was a real learning experience, not just for the students, but for the faculty, too.

TM: It was a complete change. I had done webinars and those kinds of things, but I’d never taught an entire course online. Clemente was the first time in my teaching career where I had to turn one of my courses into an online experience. It was also the first teaching that was fully disrupted for me by the COVID pandemic. There was a lot lost last spring all across the board in education. I think it’s safe to say that very few of us fully knew what was happening or what would come of it.

Among our Clemente scholars are people who have all sorts of commitments and responsibilities with family, as well as serious concerns about their own health, some with comorbidities and preexisting conditions. Some of our students are essential workers on the front line whose work is precarious because it’s part of a gig or wage economy. Some have lost their jobs during the pandemic. At this point, we should all know about the different realities of housing precarity, food insecurity, economic inequality, and health disparity. Many of our students were already dealing with these things, but the COVID pandemic has exposed all of these inequities in our society and made them worse, including access to technology. The digital divide—which is also a racial and class divide–became very clear once we had to move Clemente online. We found out very quickly who had access to WiFi, who had a laptop, who only had a phone.

JS: I remember talking to one Clemente scholar at that time who was trying to do the reading and writing assignments through her phone, and in order to get WiFi, she had to go to a different part of her apartment building, which was dangerous because of COVID.

TM: I remember that student calling into class and not being able to directly reference the assigned reading, even though she had clearly done it, because she was participating in class from the phone and the readings were also on her phone. She couldn’t do both at the same time. Other students dropped off because they didn’t have reliable internet access, or they were overwhelmed with homeschooling their children, taking care of elders, working overtime shifts on the front lines, getting sick themselves, and lacking the necessary technology to access the online course.

All of the things that we have to contend with in Clemente without a pandemic were thrown into very sharp relief and disarray once COVID hit. And that includes the faculty. For instance, Jack Cheng (Clemente’s longtime Art History Professor and former Academic Director) has two teenage children whose learning also shifted online. His wife Julie is a doctor at Codman Square Health Center and Dorchester House. Jack found himself teaching his kids at home while she was on the front lines in the community caring for patients, some of whom include our Clemente students. In my case, my brother and niece and that side of my family experienced many disruptions and needs that had never existed before in quite this way. Last spring, we all had to step up to figure out how to deal with these challenges together. My parents are retired, in their late 70s, and they live in a different state, so we were concerned about them as well.

As far as Clemente is concerned, last spring was incredibly disappointing. We felt like COVID stole the semester from us. I only had two class meetings before we went online, and then things started to fizzle out. We managed to keep a number of students in the course, and we were flexible and worked with Bard College to make sure that students could get their credits. We dialed back what we expected of them for final papers. We were able to get through and stumble to the finish line, but I don’t think anyone was fully satisfied with the experience. As a result, all of us were yearning to figure out how we could do this in a different way that would be more successful and satisfying.

I have been teaching in the Boston Clemente Course for 20 years, and I love it! Jack and I are the founding Art History and American History professors here. I served as Academic Director for most of the first ten years, Jack for the last ten, and now Ann Murphy and Julia Legas, our dear friends and longtime colleagues, are leading us. Over the summer and early fall, I did a lot of reflecting about these two decades. I get choked up when I think about it. It’s wonderful that Jack and I have had these 20 years together, and we really love and respect each other. We’re different, as you know, but that’s what makes it work. I’m going to be 50 this year, and I’ve spent twenty of those fifty years teaching Clemente. That’s 40% of my entire life, 80% of my professional academic life. My origin and evolution—as a scholar, teacher, and citizen—is deeply intertwined with Clemente and Codman Square.

None of us wanted 2020 to be the end of Clemente. We didn’t want to stumble to the finish line ever again. We wanted to reinvent ourselves, reimagine what this could look like, and that’s precisely what we did. The four of us—Jack, Ann, Julia, and me—have worked together for many years. We love each other. We have deep affection and admiration for one another as people and colleagues. Last summer we said to each other: “You know what? Let’s do this. Let’s figure this out, and let’s do it right.” And we’ve been “all in” ever since!

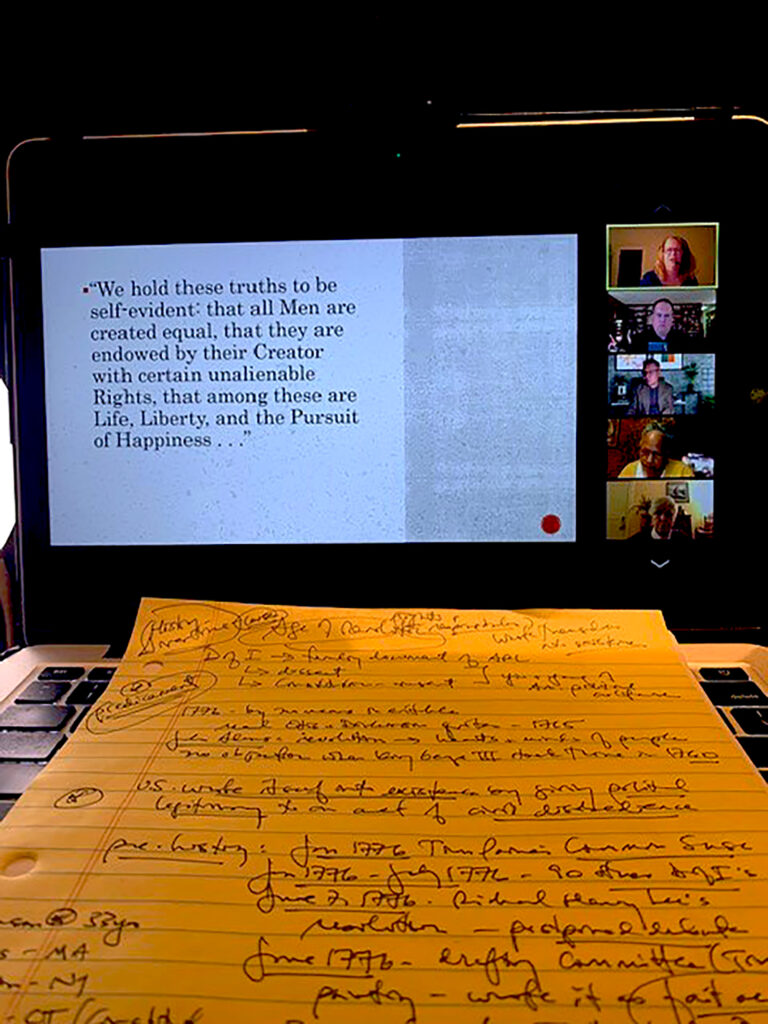

In the fall of 2020, instead of recruiting for and starting a new academic year as we usually do, we switched gears. We took stock and decided to use this historical moment—the contentious national election and perilous global pandemic—as an opportunity to talk about the Declaration of Independence with alumni and prospective new students. Our theme was “Community and Responsibility: What Do We Owe Each Another?” Over the course of ten two-hour sessions in October and November, we analyzed that founding document and related materials through the lenses of history, literature, philosophy, and art. In the first week, everyone read different parts of the Declaration, and then we discussed and wrestled with it. The fifteen or so participants were a mix of alumni from the Clemente Course for veterans, the standard Course, and a few potential new enrollees.

For my part, when we got to the American History week, I assigned materials from the 1793 Yellow Fever pandemic in Philadelphia and the 1955-56 bus boycott in Montgomery. We used the former as a case study to discuss the anti-Black racism, socioeconomic inequities, and public health issues that emerged during a time when Philadelphia was the largest, most racially diverse city in the United States, and also the capital of the United States. For the latter, we focused on the often overlooked role that Black women played in organizing one of the most successful boycotts in American history, also one of the first great “democratic dramas” of the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Every one of the 15 or so people who signed up came to all ten sessions. It was one of the best teaching experiences I’ve ever had. The students were highly energized and engaged, given the state of the world. For faculty members, it was a beacon, a sign that an online version of the Clemente Course could not only work but soar.

JS: What’s in store for spring 2021?

TM: We’ve reimagined the Clemente Course this winter and spring to four four-week sections, with two two-hour classes each week on Monday and Wednesday evenings. Jack Cheng will teach Art History, then Ann Murphy will teach Literature, then Julia Legas will teach Moral Philosophy, and then I will teach American History. I have completely reworked my syllabus for this year’s class, which I’m calling “Reckonings,” centering our work on the long Black freedom struggle from the American Revolution to the present day.

JS: Tell me a little bit more about that. What’s an example?

TM: We will focus on what I’m calling “democratic dramas,” centered around crucial conflicts involving race and racism at four major inflection points in American history. It’s more focused than my usual Clemente syllabus. Each of the weeks will have its own theme, running chronologically.

In the first week, “Race and Revolution,” we will look at Phillis Wheatley and Thomas Jefferson, the 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever pandemic, and 1790 Naturalization Act, which is the first time that U.S. citizenship was racialized as “white” and therefore restricted in “racial” terms.

Then we’ll pivot to “Slavery and Freedom,” diving into the abolitionist writings of Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and David Walker, and then moving to the Civil War and Reconstruction to look at Abraham Lincoln, more Douglass, and the Reconstruction (13th, 14th, 15th) Amendments.

The third week is “Reaction and Renaissance.” The “Reaction” part covers the end of Reconstruction and the rise of the “nadir.” We will look at the work of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. In the “Renaissance” section, we will discuss W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, and “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the Black National Anthem written by James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosamond Johnson.

The final week, “Protest and Power,” includes the women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Dr. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” James Baldwin, Malcolm X, Fannie Lou Hamer, and the Black Panther Party.

I will assign them an archive of primary texts every week and then we’ll try to make sense of it all together. This approach allows the students and me to really “dig in” and work hard to understand these pivotal moments in American history.

JS: That approach puts them into the role of being historians. “Here are the documents; here are the archives. How would you interpret this?”

TM: Yes, that’s the intention. This approach also centers race and racism, African-American history, and the long Black freedom struggle in a way that is especially appropriate right now, something that I find students are really yearning for.

JS: What do you think will happen next year?

TM: That’s the million-dollar question. I think if we can be back at Codman Square safely in person, then we’ll do that. But it’s complicated. Many in our Clemente community have real health concerns related to various preexisting conditions. That includes members of the faculty, but I’m thinking principally of our students and their family members. It’s hard to get out of the house and get to school if you still have people at home for whom you are responsible. Everything is still up in the air right now.

JS: Maybe a hybrid of in-person and online classes?

TM: There are issues of access from various angles. Once you meet the challenges of the digital divide—which is also, as I said, a race and class divide—it becomes easier to “attend” class. It is imperative that we bridge this gap, and we are grateful to Mass Humanities for raising the funds we need to help us do just that. But in the case of in-person classes, there are also different barriers, like access to transportation. Many things have changed as a result of COVID. For instance, picking kids up from school is not something our students have had to do during the pandemic, and in some cases, our students are either working from home or out of work. In this current landscape, once you meet the technological access needs, academic access becomes a bit easier. But getting from home to school in a physical sense is still a challenge, for so many reasons. Everything is constantly changing right now, uncertain and up for grabs, so we have to remain as responsive as we can. There are so many challenges.

That said, across the board in my teaching during the past year, I have found that people are extending each other an enormous amount of grace in this moment. I am trying to model that as a teacher. The regard that people are demonstrating for one another during this crisis is deeply moving, and I was struck by how generously the students and faculty engaged with one another throughout the fall. The moments of contention that sometimes surface in our in-person classes—where people roll their eyes, look at each other dismissively, go on the attack, or get self-righteous—are vastly diminished now. The community is kinder and more intentional, has deep regard and broad grace for one another. I’m not sure if it’s because of the online format, or the pandemic, or just a combination of so many things, but it’s beautiful to witness. I have long defined the humanities as the shared study of what it means to be human so we can become more humane. If Clemente is a gauge and a guide, I actually think we’re becoming better people in this time. As the Indian writer Arundhati Roy has suggested, this pandemic could become a “portal” to a vastly different and more just world.

That said, I think the ways in which we hold each other to account and regard each other in real space, in real time, with real people, in the physical presence of others, is also the stuff of community. But I’ve been rethinking the limitations of that truth. I have come to believe that we can create real and intentional communities in these virtual, online spaces. All of this comes with the crucial caveat, again, that we must close the digital divide. But once we meet the challenges of providing reliable, affordable, universal access to the internet, a new world of education is possible.

For instance, this fall, we had people Zooming in from Hawaii, Virginia, North Carolina, New York, and parts of Massachusetts outside Boston. We had people in the Zoom classroom who would not have been able to access our physical classroom in Dorchester. And that was a great thing. It built on our diversity.

JS: It’s interesting that you have “regulars,” alumni who come back to participate or who take multiple Clemente Courses like the one for veterans. One told me he was taking a Clemente Course in Seattle. That alumni connection is something to build on.

TM: The fall 2020 group was very special, in part, because they shared our disappointment in the way the last academic year had to end. We were all unsatisfied, but we were also determined. The students led a kind of rebirth. Together, we stuck with it, committed to it, and held each other accountable. It was really beautiful. In some ways, that community of faculty, alumni, and prospective students saved Clemente in Dorchester.

JS: The power of the alumni group to do that, to stay in and grow the program, to be part of it, is inspiring. Let’s take a step back. Tell me about your approach to teaching, in particular in the Clemente Course.

TM: I came of age as a scholar and teacher within the intellectual revolutions of social history and multiculturalism that were sweeping the academy during the 1980s and 1990s. Entering Harvard College, I hadn’t had a lot of that in my public high school curriculum other than what I was able to create with some exceptional teachers. But in college I was awakened to different ways of thinking about the past and its connection to the present.

Harvard had just done a “cluster hire” of leading scholars in African-American Studies, which experienced a kind of “renaissance” during my time there. I ended up taking courses in African-American history and literature and politics. I took a course on southern Africa, which was crucial for me, since I was becoming active in the student divestment movement against apartheid in South Africa.

Those years were at once an awakening and crucible, coinciding with the fall of the Berlin Wall, AIDS activism, the first U.S. war on Iraq, Mandela walking out of prison, the L.A. riots, and the political shift from Reagan-Bush to Clinton. All of those things led me to think about the dynamics of social change on the global scale: the tanks in Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Soviet Union, the end of apartheid in South Africa, the twilight of the long Reagan era.

This profoundly shaped the way I think about history. At its core, history is a contested set of stories about change over time, a way for us to understand not just the origins and evolution of society, but also the various motivations that spur these changes. Social history and multiculturalism opened up new pathways to knowledge and understanding about the diverse groups of people who have been agents of change throughout history. History could now be told from the “bottom up” as opposed to top-down.

In college, I was introduced to Howard Zinn, and I read A People’s History of the United States before I went to graduate school at Columbia University. When I got to Columbia, I studied with Eric Foner and the late Manning Marable, two of the scholars who led that revolutionary turn in African-American Studies and social and political history. My approach to teaching history has always been centered on “the people,” a multicultural approach to understanding the complex dynamics of social change in any given country, culture, and context.

JS: It’s interesting to think of that period in the late ‘80s and early ’90s as revolutionary, compared with the ‘60s, and then compared with what’s happening right now.

TM: In many ways, the ‘60s and ‘70s produced the context for that transformation within the academy, a series of social, political, and cultural revolutions, which then inspired a kind of intellectual revolution. My generation, “Gen X,” was educated—or more precisely, saved from our mis-education—in a deeply political academic and intellectual environment that was made possible by the revolutions, the turbulent insurgencies, of previous generations.

I love to hear my current students, whether Clemente students or Harvard students, talk about “intersectionality.” I like to tell them that I was studying intersectionality when Kimberlé Crenshaw first published her trailblazing law review articles and coined the term. They talk about “respectability politics,” and I tell them that I first read Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham’s amazing book, Righteous Discontent, decades ago. My students now talk all the time about “identity politics,” “respectability politics,” “intersectionality,” “de-centering whiteness” and “interrogating systemic oppression.” We were doing all of that over a generation ago. I’m glad to see the beat goes on.

My career began with researching slavery and abolitionism, the period between the American Revolution and Civil War and Reconstruction. I then became interested more broadly in histories of American radicalism over time in the United States, thinking comparatively about social movements and protest cultures. This led to my first book, The Radical Reader, and then the development of a course, “American Protest Literature,” that I taught at Harvard for near two decades. More recently, I’ve become interested in the LGBTQ movement, in part, because there’s still a real void in the curriculum but also because of my own evolving personal identities and political interests living through this particular era in history. I believe that everyone can make history and that everyone should study history. At the core of my fervent, almost evangelical love of the humanities is the idea that history is at the root of it all. It’s the core of who we are and how we understand our place in the world. We all have the opportunity to make our place in history. I like to remind my students that every history book has an index, which catalogues all the people, places, and events that have taken place in history. I ask them: where will you be in the index of the history books written 100 years from now? We should all answer that question.

JS: You mentioned that you’ve just finished a book…?

TM: Yes, it’s called Reckoning with History: Unfinished Stories of American Freedom, which will be published by Columbia University Press this summer. The book is a tribute to Eric Foner, my Columbia Ph.D. advisor. A group of us decided at his retirement party several years ago that we wanted to do a book to honor him. It’s a series of public-facing essays written by former Foner students who represent a new generation of American historians who write history in a more political way. Some of the essays meditate on how we use archives to craft counter-narratives, and some are original reinterpretations of major themes and topics. Mine is about the twists and turns of writing history and teaching history while living history at the same time.

JS: You have a lot to look forward to this year, and I can’t wait to read your book.

TM: Indeed. Slowly but surely, things seem to be looking up!