Down the Rabbit Hole of Local History

Down the Rabbit Hole of Local History

Local history librarians like me usually end up being both archivists and curators of the collections we oversee. In addition to organizing and servicing collections under our watch, we are tasked with making decisions about what items and collections to add. We make these decisions based on the context of existing collections (does the item or collection relate to others already in our possession?) and in anticipation of what we think people will want to use and see in the future. We are also charged with making the collections in our possession breathe by demonstrating their ability to add to our understanding of the world. We do so in the hope that others will follow our example and discover new ways to use and think about the collections under our care.

When I look back on the exhibits that I have created over the years both here in Westborough and at other institutions, most of them were about subjects where I had little knowledge and only a tangential interest. In some cases, the idea for the exhibit was suggested to me by someone else, and I added my own spin once I started working on it. In others, the collection itself demanded to be featured in some kind of exhibit due to the quality of the items in it, the interest level on the part of the community, and its importance in relation to other collections. But in every case, what started out as a task ended up a passion as I continued going down the rabbit hole of the collection and its subject-matter.

A couple years ago, the Robert Cleaves Collection of Lyman School Records (LH.070) was donated to our library, and as soon as I opened the box and started going through its contents, I knew that I had to create an exhibit around it. The collection contains the first volume of meeting minutes for the Trustees of the Reform School—the first state-run reform school in the country and what later became the Lyman School for Boys (both iterations were based here in Westborough). The collection also has printed reports and promotional materials for the school and, most importantly, pictures of the boys taken between the years 1905-1912.

I was originally planning to create a small exhibit inside the Westborough Center using the collection, but when I told Lynne Soukup, the Assistant Library Director, about my plans, she excitedly offered the entire wall in the main room of the library to me. Give any academic like me space, and we are going to fill it! My exhibit project suddenly had the potential to become something much bigger and more significant.

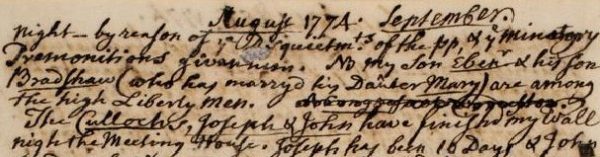

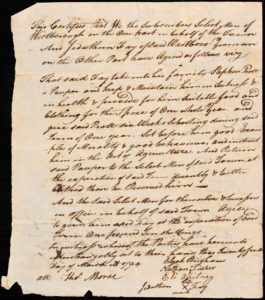

When I started to think about expanding the scope of my exhibit, my first thought was to pair these materials with a collection of indentured servant contracts I had always wanted to feature in some way. Back in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, children who became wards of the town due to poverty or other circumstances were placed as servants in families who lived in and around Westborough. Such a practice was common in colonial America, and such agreements were governed by a written contract. Both these records and those of the Lyman School document two different approaches to helping children with similarly troubled backgrounds. What accounts for the difference? Why was the practice of pauper apprenticeship replaced with a more institutional approach to child welfare? And what do these differences tell us about how people thought about childhood itself?

In talking about my expanded ideas to Maureen Amyot, the Library Director, I speculated how the two approaches to child welfare could provide insight into how childhood was thought about at these two points in history. After all, any decision about how best to help a troubled child is necessarily informed by an idea of what constitutes a “normal” childhood. Maureen loved the idea and encouraged me to pursue it.

While researching the topic, I discovered how the concept of childhood itself went through substantial change in the nineteenth century. Indeed, ideas about childhood continue to evolve today, so that, from our perspective, the treatment of troubled children in early America and in the early twentieth century both seem cold-hearted at best. But in both cases more is going on than apparent cruelty: a different idea of what constitutes childhood is at play, so we need to think more about the historical context while assessing the successes and failures of the two approaches. We may still end up criticizing them, but we will better understand the motives behind the policies and better identify their true failings.

Needless to say, the more I dug into this topic, the more interesting I found it to be. I hope you take the time to visit the Westborough Public Library to explore “Changing Pictures of Childhood: A Comparative History of Child Welfare in Westborough” or visit the online version through the link. The exhibit begins in the main room of the library and ends in the Westborough Center with a 26 minute movie that illustrates life at the Lyman School in 1946. And don’t miss the “exhibit extras” included in the display case outside of the Westborough Center. The physical exhibit will be on display until the end of September.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Recommended Reading:

* * *

On the Beaten Path Is Now Available Online!

On the Beaten Path, Kristina Nilson Allen’s history of Westborough, has been considered the standard history of our town since the time it was published in 1984, and now it is available online. The digitization of her book by the Internet Archive now gives unprecedented access to the wealth of information that Allen put together about our town.

The writing of town and county histories became popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many of them were spearheaded by publishing companies who saw them as a way to capitalize on local pride of place. The companies enlisted local, amateur historians to write them, sought local business titans to fund the printing (in exchange for including their names in the town history), and in some cases used formulaic language and statistics to pad the content. Westborough published its own town history in 1891, The History of Westborough, Massachusetts by Heman DeForest and Edward Bates, which is also available online.

To capture the historic highlights, personalities, and development of “the Hundredth Town” for her book, Allen interviewed 65 residents who remembered Westborough from the early 1900’s on. Town officials supplied the background of their departments, while merchants and manufacturers told the story of Westborough’s economic growth. A new archeological study, completed by Prof. Curtiss Hoffman, filled in Westborough’s prehistory dating back 6,000 years.

The digital version of On the Beaten Path includes the ability to search the content of the book for keywords, download the text in multiple formats, and have the book read aloud for the visually impaired.

* * *

The Westborough Archive Catalog Has a New Look

If you are interested in exploring the archival records of Westborough, the Westborough Archive Catalog is the place to search. And now it has a new interface that makes searching even easier. The catalog lists all of the collections housed in the Westborough Center and includes links to any online content or finding aid associated with the collection. Here’s your chance to experience real history and work with historical records like an historian!

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Local History Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox: https://www.westboroughcenter.org/subscribe-to-updates/.