Mar 16, 2022

Sharing updates and discoveries.

March is Women’s History Month. While I think that every month is an ideal time to research, talk about, and value women in every facet of our history, I will always embrace the opportunity to join a broader conversation about the stories of women’s lives. This month, I find myself thinking about women’s work, labor organizing, and the historical relationship between women and textiles. Naturally, I’ve been tracking union labels in women’s garments in the Historic New England collections. Thus far, I’ve found two labels that reference the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU): a light pink polyester sweater shell worn by Ripley “Rip” Miller and an organza wedding dress with a taffeta underskirt and a beaded lace insert worn by Virginia Ramsdell (Vasiliou). These garments date from the 1960s, but they speak to a longer history. The ILGWU, formed in 1900, was built from the organizing of predominantly immigrant women working in the textile trades and it’s an incredibly important part of the history of labor organizing in the U.S. It also tells us a lot about ideas about women’s work.

The label on Ripley Miller’s sweater

This label features a mixture of text and iconography. It is densely packed with information, but still relatively visually simple. It proclaims, in bold, unadorned text: “Int. Ladies Garment Workers, Union Made.” A series of letters hover above the central emblem: YBAE. These letters indicate that the clothing was made by Local 155 in New York, known as the Knitgoods Workers’ Union. The design of the label suggests that the garment was made between 1964 and 1973, but the text is not the only source of information.

The name of the ILGWU is surrounded, although its scalloped perimeter is interrupted. Where the eye might anticipate the rest of the border, the image of a needle reframes the printed line as stitches. The border swoops into the eye of the needle, announcing itself as thread. The needle’s nose appears to pierce through the fabric of the label, the ink that builds its body stopping suddenly. The icon is a clever visual trick, suggesting its own creation in an act of stitching.

Importantly, while this icon suggests an act of hand stitching, the garment was made by machine. One might call it a mass-produced sweater. The label asks us to reconsider our assumptions about machine-made clothing and to remember that human hands are still involved. Specifically, this iconography was part of a much broader campaign to ask American consumers to think about the women who made their clothes. Not all ILGWU workers were women, but it was composed of mostly women for much of its history and it regularly emphasized the femininity of their work in strategic ways.

Garments, quilts, samplers, needlework pictures, and other forms of textiles are often considered feminine objects, even if made for men. Historically, many of these objects were the product of unpaid labor within the home. Women and girls were expected to take this on as part of their “natural” role within the household. As unpaid work, this domestic stitching was literally devalued, but it also acquired a nostalgic sheen. Romantic ideas about women’s domestic hand-stitching proliferated in the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, as industrialized textile production took hold.

These associations between women and textiles also meant that paid textile labor within an industrializing economy could be undervalued and exploited. Employers often spoke about women’s affinity for textile labor, drawing on longstanding tropes about the relationship between femininity and cloth. By emphasizing women’s “natural” connection to cloth, employers could downplay the skill and training that this work required. These forces pushed women into textile trades and kept wages low, but women within these trades refused to accept the division between the machine and the hand. They raged against the notion that women’s unpaid hand-sewing should be romanticized and considered worthy of protection, while their textile work in a factory should go unregulated and ignored. Garments made in factories are still handmade; they require the labor of people’s hands. The ILGWU label makes this argument cleverly.

Mobilization in the workplace

The ILGWU was formed in 1900 in New York City and mobilized workers engaged in making women’s clothing. These workers, many of them eastern European and Italian immigrants, sought to resist the unsafe, unsanitary, demeaning, and underpaid work conditions that characterized the industrializing garment industry.

Clara Lemlich, a member of the ILGWU, took the stage in New York in November of 1909, as shirtwaist makers gathered to debate a proposed strike. Lemlich, a Jewish immigrant born in Ukraine in 1886, raised her voice in Yiddish:

“I am a working girl,” she said, “one of those striking against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here for is to decide whether we shall strike or shall not strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared now.”

The ILGWU supported the nearly 20,000 shirtwaist workers who went on strike over the next two months. Another strike in 1910, known as “The Great Revolt” of nearly 60,000 cloakmakers, further cemented the ILGWU’s place in the labor movement.

These strikes ended with the “Protocol of Peace,” which stipulated, among other things, that workers should not have to pay the electricity bill for the machines they used while manufacturing garments, that the work week be capped at six days and not exceed fifty hours, and that working conditions be monitored by a joint board with union representatives. Conditions were still deplorable, as the terrible fire in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory revealed later that year. But the ILGWU continued to organize; its female membership grew throughout the 1930s and 1940s as more women entered the workforce. By the mid-1930s, New England membership was strong: Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine were all covered by the ILGWU Cotton Garment and Miscellaneous Trades Department. Today, the ILGWU is known as UNITE HERE, the result of a 1990s merger with the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers and a 2004 merger with the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union.

Campaign for the union label

By 1959, the ILGWU launched its “Union Label” campaign, telling customers to look for garments labeled as union made. The ILGWU had used an optional label since its inception in 1900 and frequently called for garment industry-wide labeling requirements. Yet these efforts remained haphazard until this new, concerted campaign adopted savvy use of new media forms. And from 1959 until the merger in 1995, the label changed many times, but the threaded needle stitching its waving border remained in every iteration.

At the start of the campaign, the ILGWU staged photo ops with women like Eleanor Roosevelt sewing a union label into an item of clothing. These photographs typically featured a prominent woman sewing by hand.

Factory workers became the major faces of the campaign in the 1970s. Lillian Armour, a young woman from Waterbury, Connecticut, and the daughter of Italian immigrants, became a face of the “Look for the Union Label” campaign when it launched in 1975. She’d worked in the garment trades since the mid-1940s—except for the first ten years of her daughter’s life—and was a member of her local chapter of the ILGWU. Members also formed the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Label Chorus and they performed at labor events and in broader media efforts, often surrounded by sewing machines.

In a series of print, radio, and television ads (complete with a jaunty jingle), this 1975 campaign called on consumers to:

“Look for the union label/ when you are buying a coat, dress or blouse./ Remember somewhere/ our union’s sewing,/ our wages going/ to feed the kids and run the house.”

Even though this campaign did not explicitly reference textile labor as women’s work, it reinforced the idea that the people making American garments were working mothers, women whose pay would help them “feed the kids and run the house.”

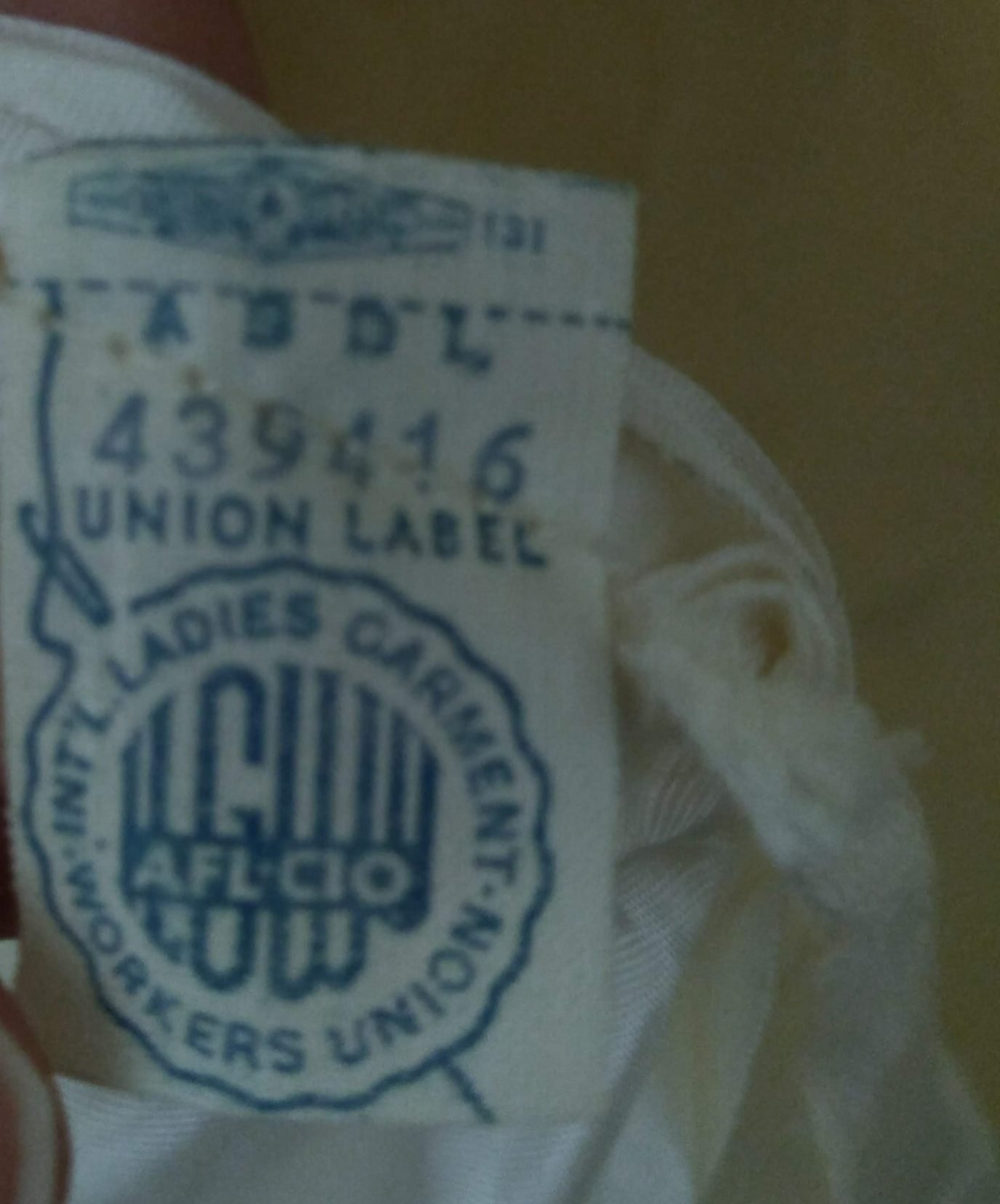

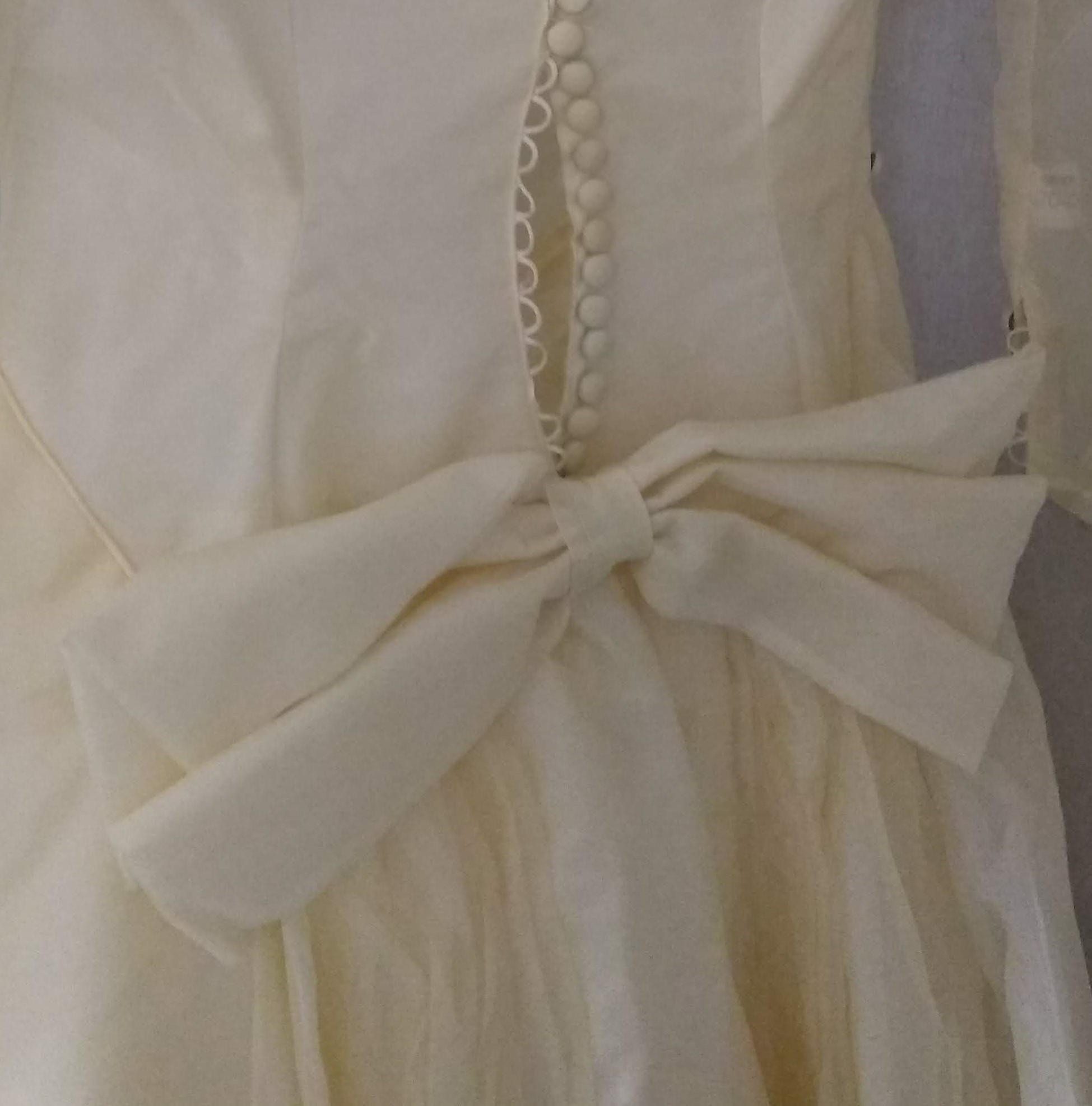

More about the garments

The garments marked with an ILGWU label in the care of Historic New England were important to the women who wore them. And those stories are worth knowing, worth telling. I look forward to learning more about these people and how these garments helped them construct an identity, a moment, a memory. Virginia Ramsdell wore this dress when she married William Theodore Vasiliou in 1962. Rip Miller often wore this sweater with a white knit suit when she flew. She was a licensed pilot and a proud member of the Ninety Nines—an international organization of women pilots, once helmed by Amelia Earhart. (Learn more about Rip Miller in the Winter 2017 issue of Historic New England). These stories are meaningful and these clothes help us tell them. I am also struck by the importance of these little labels. These small, printed tags ask us not to forget who made the clothing that we wear.

Women in New England participated in the ILGWU throughout the twentieth century, eventually making the clothes that Rip Miller and Virginia Ramsdell wore in the 1960s. The garments meant enough to Ripley and Virginia and their families that they were eventually placed in the care of Historic New England, meant to be preserved and remembered as emblems of their lives. But these labels leap out to me, though they’re quietly contained inside each garment, meant to be pressed close to the wearer’s body. They insist that we read these garments not just as ways to access the wearer’s story, but as ways to give specificity and nuance to our ideas about factory-made clothing. They remind us that cloth speaks of power and that everything we own was made by someone, somewhere. They ask us not to forget the work of the hand.

Mariah Gruner, Ph.D. is the Recentering Collections Curatorial Fellow.

Over the course of her IMLS grant-funded fellowship, Mariah Gruner will work with the Collections Services team to draft a new collecting plan and develop a body of research that explores marginalized and suppressed stories within Historic New England’s existing collections. Mariah will share monthly updates about the collecting plan and her research over the course of her ten-month stay.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.