by Local Historian Kristina Nilson Allen

Note: The following group of essays is taken from Kristina Nilson Allen’s Westborough Historical Society program held on January 9, 2023. You can view her talk here: http://westboroughtv.org/famous-women-of-westborough-across-the-centuries-with-kris-allen/.

Across the centuries, these five women broke barriers to pave the way for Westborough women today:

- 1700s – Betsy Fay Whitney

- 1800s – Annie Fales

- 1900s – Esther Forbes and Bee Warburton

- 2000s – Nikki Stone

Betsy Fay Whitney (1867-1972), Entrepreneur

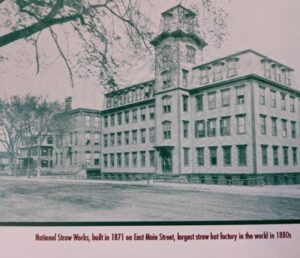

Betsy Fay earned her dowry by starting a straw hat business. Later, her son Eli (future inventor of the cotton gin and interchangeable parts manufacturing) aided her by making long hair pins and a head mold.

In the 1880s, Westborough’s straw hat business became the largest in the world.

Annie Elizabeth Fales (1867-1972), Westborough School Teacher

Annie Elizabeth Fales (1867-1972) was born in Walpole on July 17, 1867, and moved to Westborough at age 7. She was an 1885 graduate of Westborough High School and went on to earn her teaching credentials at Worcester Normal School (now Worcester State University).

After graduating in 1887, she taught in Upton a short time and then returned to Westborough. Annie Fales lived most of her life at 58 West Main Street, across from the Library. Her home was filled with the aroma of homemade cookies and baked beans, which she shared with neighbors. Active in the community, Annie Fales was a member of the Women’s Club, Garden Club, Historical Society, and the Round Table.

Her first hometown assignment in 1892 was teaching in the one-room District 8 School House near Lake Chauncy. Miss Fales taught grades 5 through 8, and when the Eli Whitney School opened on Grove Street in 1902, she was named its principal. A lifelong love of music motivated her to take voice lessons in Boston, and she learned to play several instruments. She was a soloist in the Unitarian Church choir, as well as the organist. Many special events at the High School were enlivened by Miss Fales’s piano accompaniment.

At age 95, she shared her philosophy of teaching: “Patience, a sense of humor, and a real love of children—that makes a good teacher.”

On December 2, 1963, the first Annie E. Fales Elementary School opened on Eli Whitney Street. A newly constructed, environmentally progressive Fales School opened on November 15, 2021 with 381 students, grades K-3. Both schools honor Annie Fales, who dedicated her life to teaching for more than a half-century in Westborough

She retired in 1937 and lived to be 104. Annie Fales died on March 3, 1972, and her memory is honored in the elementary school that bears her name. Over the span of her career, Annie Fales molded the lives of more than 1,000 Westborough students.

Esther Louise Forbes (June 28, 1891-August 12, 1967), Author

Esther Louise Forbes was born in Westborough at 39 Church St., home of her parents, Judge William Trowbridge Forbes and Harriet Merrifield Forbes. Esther attended the elite Bancroft School in Worcester and later graduated in 1912 from Bradford Academy, a junior college in Haverhill.

Always interested in literature and writing, Esther published her first short story, “Breakneck Hill” in 1915. It won the O.Henry Prize as one of the year’s best short stories.

Esther’s reputation as a fine new author grew rapidly. Her first novel, O Genteel Lady, published in 1926, was selected for the newly created Book of the Month Club. Esther specialized in writing a series of historical novels, all set in New England with courageous female heroines. Over her career, she wrote 11 books: 8 historical novels, one biography, and two pictorial essays.

Esther’s novels claimed critical attention. The 1928 A Mirror for Witches chronicled the life of Dilby, a young woman destroyed by ignorance and prejudice during the Salem witch trials. It was adapted for the stage, including a ballet in 1952 and an opera titled Dilby’s Doll in 1976. She received the 1947 MGM Novel Award for The Running of the Tide.

Esther Forbes was also a serious intellectual historian. She eventually lived in Worcester with her mother, the noted historian Harriet Merrifield Forbes, who had written a history of Westborough titled The Hundredth Town in 1889.

Harriet Forbes and her daughter worked as a team. Harriet did much of the historical research for Esther’s books at the prestigious American Antiquarian Society. Esther went on to win the 1943 Pulitzer Prize for History for her definitive biography, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In.

Harriet Forbes and her daughter worked as a team. Harriet did much of the historical research for Esther’s books at the prestigious American Antiquarian Society. Esther went on to win the 1943 Pulitzer Prize for History for her definitive biography, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In.

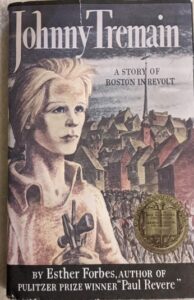

The novel that Esther is most known for, however, is the young adult fiction, Johnny Tremain: Boston in Revolt, set during the American Revolution. Johnny Tremain, an apprentice to a Bostonian silversmith, witnesses the conflict between the Patriots and the Tories, as well as the battles of Lexington and Concord.

Still treasured as a classic, Johnny Tremain won the Newbery Medal in 1944 for its major contribution to children’s literature. It was even made into a Disney movie.

Still treasured as a classic, Johnny Tremain won the Newbery Medal in 1944 for its major contribution to children’s literature. It was even made into a Disney movie.

In 1960 for her contribution to the arts, Esther Forbes was elected as a Fellow of the Academy of Arts and Sciences and became the first woman to be elected to the American Antiquarian Society.

Esther Forbes died at age 76 and is buried in the Forbes family plot in Westborough’s Pine Grove Cemetery. Her papers and manuscripts were donated to Clark University, and the royalties from her work were donated to the American Antiquarian Society.

Beatrice A.Warburton (1903-1996), Iris Hybridizer

Bee Warburton, the internationally renowned iris hybridizer, majored in chemistry at Barnard College in the 1920s, where she planned to become a doctor. Tragedy struck when her father died unexpectedly when she was a sophomore, so Bee dropped out of college to help her six siblings with family finances. Despite this adversity, Bee never lost her desire to learn through research, conducting experiments, and writing about her findings.

After Bee married Frank Warburton, an MIT graduate, the couple settled in 1948 on the East Main Street farm of Frank’s father, who was a successful chicken farmer, where Mugford’s Florist Shop stands today.

Bee decided she would try her hand at gardening with help from her husband. When she couldn’t locate the dwarf iris she desired, Bee’s scientific training kicked in. She adamantly refused to give up. She decided to hybridize her own iris and to become an expert in iris genetics.

Bee decided she would try her hand at gardening with help from her husband. When she couldn’t locate the dwarf iris she desired, Bee’s scientific training kicked in. She adamantly refused to give up. She decided to hybridize her own iris and to become an expert in iris genetics.

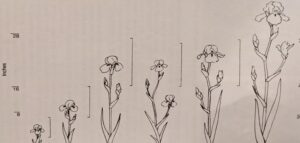

Through meticulous work with a tweezers and magnifying glass, Bee became adept at transferring pollen from one iris to another to create a different breed of iris.

One of her successful early experiments resulted in a chrome yellow dwarf iris that she registered as “Brassie” in 1957. Another early success was the “Blue Denim” iris. Over the next 38 years, she continued to hybridize dwarf irises and later in the 1970s tall bearded Siberian irises.

Bee Warburton registered and introduced to the world over 100 unique irises by crossing different colors, shapes, sizes, and petal details. On a quarter of an acre, plots of parent plants and seedlings stretched out beside the long Warburton driveway. By the late 1980s, there were 4,000 irises growing in her Westborough fields.

Bee’s irises won accolades all over the world. She was awarded the American Iris Society’s Hybridizer’s Medal seven times and the AIS Distinguished Service Medal in 1972. Over the years, Bee enjoyed hosting iris auctions that attracted iris experts to her rainbow-hued fields. The proceeds from these auctions were donated to the Massachusetts Iris Society.

Bee may have made an even greater contribution to iris gardeners by her writing, editing, and publishing about iris genetics. She wrote articles for the New York Times and for international iris journals. For 20 years she served as editor of the iris publication, The Medianite, and appeared on the 2007 cover of its 50th Anniversary issue. One of her most important accomplishments was her editing of the classic, The World of Irises (1979), which is in its third printing today.

Bee may have made an even greater contribution to iris gardeners by her writing, editing, and publishing about iris genetics. She wrote articles for the New York Times and for international iris journals. For 20 years she served as editor of the iris publication, The Medianite, and appeared on the 2007 cover of its 50th Anniversary issue. One of her most important accomplishments was her editing of the classic, The World of Irises (1979), which is in its third printing today.

To this day, Bee Warburton irises are grown in Europe, Asia, and Africa. It is believed that the majority of dwarf irises around the globe share some DNA with Bee Warburton’s irises.

Bee has remained an icon in the international circle of iris hybridizers long after she died in January 1996 at age 92. The greenhouse at Westborough High School was named for her in 2002.

Bee Warburton was known for being kind, witty, generous, and most of all, persistent. She didn’t sell her irises, but delighted in giving them away. Bee Warburton’s colorful legacy, born in Westborough, continues to bloom each spring the world over and in our local gardens.

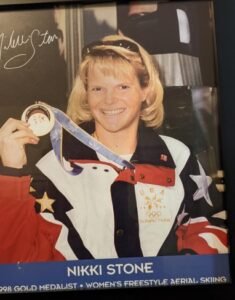

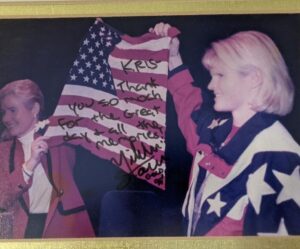

Nikki Stone (1971 – ), Olympic Gold Medalist

Westborough native, Nikki Stone, won the Olympic Gold medal in aerial skiing at the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, Japan.

Over her skiing career from 1995 on, Nikki was awarded 35 World Cup medals, 11 World Cup titles, two Aerial World Cup titles, and four National titles. In addition, Nikki was the first inverted aerialist skier ever to become the Overall Freestyle World Cup Champion in 1998.

Nikki Stone grew up in Westborough and early on began to practice gymnastics. When she was five, after seeing teen gymnast Nadia Comaneci win Olympic gold in 1976, Nikki declared that she, too, was going to win a medal at the Olympics someday.

Always the daredevil, at home Nikki practiced flips from heights and landing on a mattress. She loved being airborne. Nikki also enjoyed recreational skiing, so when she saw aerial acrobatics at 18, she realized that aerial skiing was the perfect blend between gymnastics and skiing.

After graduating from Westborough High in 1989, Nikki went on to study at Union College in New York. She then earned a master’s degree in Sports Psychology–graduating summa cum laude–from the University of Utah. In 1994 Nikki settled in Park City, Utah, where she trained seriously for the Olympics in inverted aerial skiing, where competitors ski onto a ten-foot snow jump at 40 mph, flip or twist to a height of 50 feet, and then land on a 45-degree hill.

Four years later at Nagano, Nikki performed a single twisting, triple somersault perfectly, jumping as high as a four-story building, to place first in aerial skiing. With that performance, Nikki Stone became the first American ever to win the Olympic gold medal in inverted aerial skiing.

After Nikki became an Olympic gold champion, Westborough held a Homecoming Parade for her on March 21, 1998, and proclaimed “Nikki Stone Day” to show its hometown pride in this indominable golden athlete.

Winning the Olympics generated a lot of interest in her success, so Nikki was engaged to speak all over the country. Nikki discovered that much of what she learned from sports translated directly into the business world. Today, she speaks to nonprofits and corporations to encourage their employees to achieve their best, take risks, and overcome difficulty. An award-winning motivational speaker, Nikki draws on her own experience of triumphing over adversity.

Her inspirational story: After winning 48 World Cup medals in aerial skiing, Nikki sustained an inoperable back injury. Ten doctors said she would never ski again. Eighteen months of training and rehab later, Nikki was competing in the 1998 Winter Olympics. Through pure determination and courage, she won the gold.

In 2003, Nikki was inducted into the National Ski Hall of Fame. Her book, When Turtles Fly: Secrets of Successful People Who Know How to Stick Their Necks Out, was an Amazon bestseller in 2010 after Nikki introduced it on The Today Show.

“One of the most rewarding times for me,” confides Nikki, “is when someone comes up to me after a speech and tells me that they are going to change their life because of something I said. To have an impact like that on someone is awe-inspiring.”

Nikki Stone has made a career of being awe-inspiring—first on ski jumps and now behind the podium.

From business to athletics, from science to the arts, these women pioneers have been role models for Westborough women today.

From business to athletics, from science to the arts, these women pioneers have been role models for Westborough women today.