This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

Trade and the Global Economy, Part I: The Commodification of Eastern North America

Europeans discovered the existence of American lands right at the time when they had begun to realize the vast wealth that could be accumulated through international trade, most notably with India and other Asian countries.* With “dollar signs” in their eyes, they immediately thought about these new lands in similar terms. But European pursuit of wealth accumulation in the Americas took on a different form from the one they practiced in the Middle East and Asia. On this side of the world, Europeans focused more on the extraction of natural resources than on trade with existing cultures.

Spain—which enjoyed a short head-start when it came to the Americas—set up a formalized system of state-sponsored conquest and exploitation throughout the Caribbean, Mesoamerica, and into South America that mainly targeted gold and silver. This system resulted in huge volumes of precious metals flowing into its government coffers, while other European powers watched with envy. But the French, the Dutch, and eventually the English—all of whose explorations were mainly confined to North America—ended up creating more flexible commercial systems than the Spanish. Their systems relied on private investors rather than on government-funded enterprises to carry out their country’s colonial ambitions. These private investors sought quick returns on the money they put up for exploring and exploiting any valuable natural resource that could be found on the other side of the Atlantic. Both of these colonial systems had devastating effects on the Native peoples who were living in these lands. But whereas the brutality of the Spanish Empire on Indigenous populations was on full display to the world, the colonial methods used by the French and English were slower to take effect and, consequently, slower to reveal the full impact that they would have on the people who had lived in the Americas for millennia.

Whether willing or not, as soon as Native Americans met the Europeans landing on their soil, they entered a global trade network. This trade network would ultimately shape European colonization, shift military balances, create transatlantic empires, upend the ecology of North America, and forever alter the consumer worlds of both cultures. A new world order was about to be put in place.

The years when the English attempted to establish permanent colonies in North America—Jamestown in 1607; Plymouth in 1620; Massachusetts Bay in 1630—are so established in our heads that we often neglect to recognize that before this time both Native Americans and Europeans had already been living and trading together for well over a hundred years. Even more, we fail to note that Native Americans had been engaging in trade throughout North America for thousands of years before European arrival. The people who lived in the Charlestown Meadows here in Westborough possessed tools and stone flakes that were made near Boston and north of the city as well as in eastern New York State. These early Westborough residents either had traveled to these places or had conducted trade with people who were connected to these areas in some way.

Trade conducted among Native Americans was different from that of Europeans in that its aims were not acquisitive, individualistic, and profit-seeking. Instead, their trade reflected universal Native attitudes towards property rights, where need and use were highly prized. In this system, individual acquisition was frowned upon. If you and your family had more food, clothes, tools, etc. than were needed, you were expected to share or give the excess to those who were in need. Hoarding was considered a form of antisocial behavior. In this framework, status was conferred not on those who possessed the most (as is the case in our society today), but on those who gave away the most. As one Dutch colonist explained about Native American leadership, “The chiefs are generally the poorest among them, for instead of their receiving anything . . . these Indian chiefs are made to give to the populace.”

Contrast this attitude towards possessions and resources with that of Europeans, whose economic activity centered around the commodity—a concept that originally evolved out of increasing scarcity of land and resources across northern Europe. The abundance of resources found in North America had comfortably supported people for thousands of years. But now these resources were divided up and treated as individual commodities with prices (which itself is a measure of scarcity). These commodities could then be converted to money and consequently be used to obtain other desirable European goods. Since labor to extract these resources was scarce in the Americas, which made the accumulation of capital that much harder than in Europe, colonists compensated for this discrepancy by exploiting the land as much as possible. With a scarcity of fish, fur, and lumber back in Europe, these essentially free goods on the western side of the Atlantic could simply be transported back to Europe in order to realize a substantial return on the labor needed to gather them. The more that could be gathered with as little labor cost as possible, the greater the profit. (This principle led directly to the development of the transatlantic slave trade. After Europeans quickly realized that it was a bad idea to enslave Native Americans on their home turf in order to minimize labor costs and increase profits because they could easily rebel, they instead sent them down to the Caribbean to work and imported Africans to work as slaves instead on their newly acquired land.)

While increasing trade volume was the primary economic goal for Europeans, it had always been kept in check among Native Americans by two factors: by need, because there was little sense in making or trading for more than what a village could eat or use; and by the sachems, who were tasked with maintaining balance within and among villages. But as Indians developed trade relations with Europeans, an abstract set of equivalent measures started to be put into place and guide their trading practices: numbers of pelts, bushels of corn, fathoms of wampum, and, most notably, currency value expressed in British sterling, a value that was governed far overseas in London markets. Native Americans, European colonists, and European manufacturers were all becoming linked, and what linked them all together were prices. Native Americans soon learned that certain things in their natural environment now had a price, something that did not exist before European arrival. This new economics also impacted the culture of Indigenous people: personal prestige, which before had to be earned through good deeds, could now simply be purchased by killing animals and exchanging their fur for wampum or high-status European goods.

In the years leading up to this point, neither the Europeans nor the Native Americans could have clearly grasped the consequences that this new economic system would have. As more permanent European settlements began to be put in place and substantial numbers of people arrived from overseas, these new economic developments in North America would have a devastating impact on the environment and on the people who had made it their home for thousands of years.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

* To learn more about the early history of international trade between England and India, see my previous Westborough History Connections series, “How Does History Connect Westborough and India?”

Works Consulted:

* * *

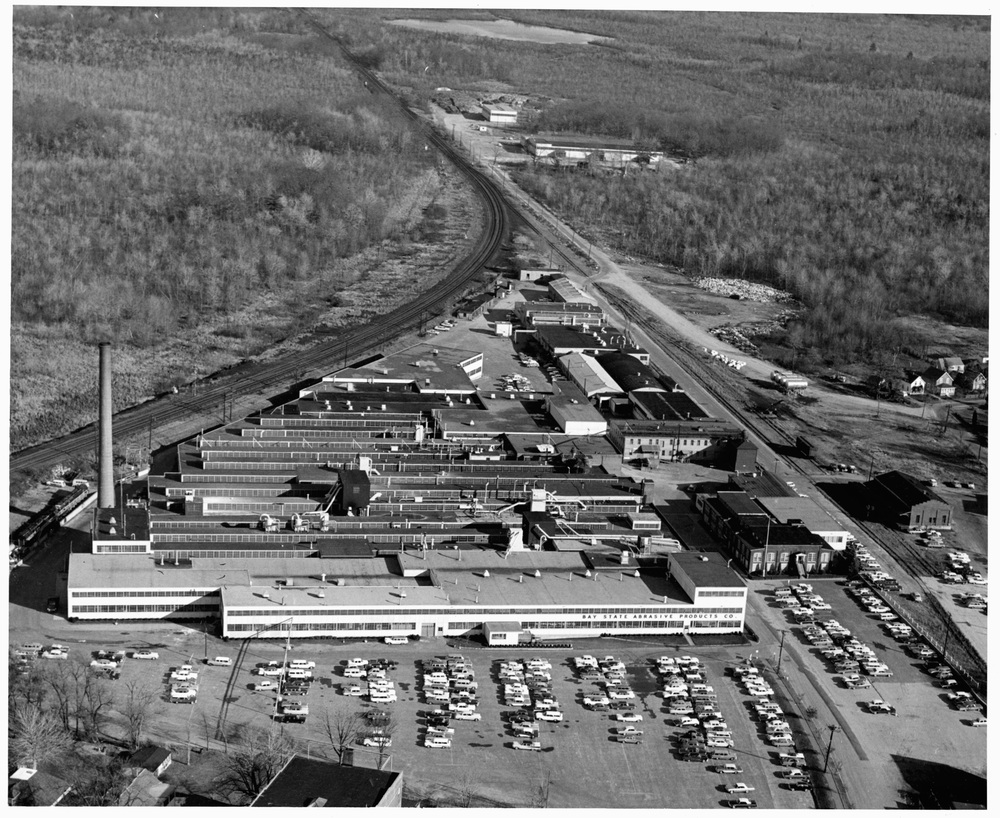

Mini-Exhibit: The Bay State Abrasives Company

The display case outside of the Westborough Center currently features the history of the Bay State Abrasives Company, which used to be located where the Bay State Commons is today. The company made grinding wheels and other abrasives for the automotive, steel, aerospace, and metalworking industries and for decades served as the town’s largest employer in town up until the 1960’s, at one point employing over 1,100 people.

The display shows newsletters from the complete run owned by the WPL and pictures of the factory and its employees that show how important this business was to the life of our town.

* * *

Nature Notes

Yikes! There’s a bunch of snakes warming themselves on a rock in the sun. Run away! Run away!

Not so fast, says Annie Reid. Our local snakes are nothing to fear!

Learn more about snakes and other natural wonders happening this month here in Westborough in Annie Reid’s Nature Notes for June.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.