This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

Land Use, Part I: Contrasting Philosophies and Conceptions of Property

The Native Americans and Europeans who met in North America starting in the fifteenth century held contrasting philosophies and epistemologies (theories of knowledge that form the basis of what counts as truth), especially when it came to ownership and land use. These contrasting belief systems were not simply a matter of disagreement or pointless rhetorical mind-games but had real-world consequences in how these two groups ultimately related to one another.

Under the banner of Western Civilization, which traces its lineage back to the Ancient Greeks, Europeans tend to divide their perceptions of reality into separate categories and then measure them, an epistemological practice that continues to this day. Europeans divide history into various historical periods that serve to characterize the social development of the specific people under consideration. They create complicated systems of classification to identify plants and animals by their biological and evolutionary relationship to one another. Even in spiritual matters, they divide up the days into weeks and then use one of those days to worship their god in a church that is designated for that practice. Then everyone goes back to their lives and works at their jobs for the rest of the week until the next day of worship rolls around.

For Native Americans, though, everything is related to the sacred, and so their reality cannot be divided up into bits and pieces. Because every single person, place, and thing is a manifestation of the Great Spirit and is thereby related to one another, inclusion and holism characterize the reality of indigenous Americans rather than division and categorization.

These two divergent epistemologies affected the exchange of material items. Under the European paradigm, material objects are separated from the spiritual world, which allows every item to be reduced to an expression of monetary value, where money serves as the main currency in most exchanges. But under the Native American paradigm, such exchange theoretically cannot happen because the material value of an object can never be divorced from its sacred value. In this case, the currency that governs the exchange of material objects always has a spiritual element. We cannot define wampum by simply comparing it to European money; rather, the intricate collection of patterned beads represents spiritual good faith on the part of both its giver and its receiver. Wampum is more an expression of personal reputation and one’s ability to follow through on promises of exchange than of any inherent value possessed by the wampum beads themselves.

These two approaches towards value and exchange also manifested in differing epistemologies relating to property and property rights—a philosophical difference that perhaps had the most consequential outcome regarding relations between the European and Native American groups.

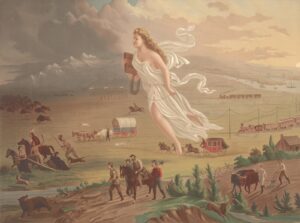

Europeans arrived in North America holding an “international legal principle” known as the Doctrine of Discovery. Rooted in ethnocentric ideas of European and Christian superiority, the doctrine held that Europeans automatically acquired property rights—which included governmental, political, and commercial rights—over the lands of any indigenous people by virtue of simply showing up and claiming to have “discovered” the land.

The concept of property is important here, because Europeans see it as forming the basis of civil society, where government’s central role is in securing and protecting a marketplace where value can be accumulated by individuals through their labor on the property that they hold. John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government (1690), essentially codified this premise philosophically, and he used Native Americans as an example of people who fail to combine their property with labor to create value:

There cannot be a clearer demonstration of any thing, than several Nations of the Americans are of this, who are rich in Land, and poor in all the Comforts of Life; whom Nature having furnished as liberally as any other people, with the materials of Plenty, i.e. a fruitful Soil, apt to produce in abundance, what might serve for food, rayment, and delight; yet for want of improving it by labour, have not one hundredth part of the Conveniencies we enjoy: And a King of a large fruitful Territory there feeds, lodges, and is clad worse than a day Labourer in England. (Chapter 5, Paragraph 41)

Locke mused that if these (Native) Americans only had money and commerce, which create incentives to work, then they would be rich and could take in all the comforts enjoyed by Europeans.

Except that Native Americans did not see themselves as poor or lacking in comfort. In fact, quite the opposite, because the land provided all that they needed, and in many ways they lived better lives than most Europeans, both in North America and back in Europe.

As we have already seen in this series, the Nipmuc annually moved to different parts of New England to take advantage of the seasonal offerings of its various landscapes. In this context, the concept of owning property does not make any sense. Sachems did claim sovereignty over areas controlled by their tribes, but these territories were more a symbolic possession tied to economic subsistence than any ownership of real estate. Any indigenous group passing through such lands could do so without worry, because the land was not something that could be owned and therefore controlled in such a way.

Possession of property for Native Americans was essentially defined by the use of land, land that could easily be abandoned for a better one if it no longer produced what the village needed. Ownership of personal property was defined by what people could make from the land using their own hands, and since women and men produced different things, they owned different objects: women owned baskets, mats, kettles, and hoes, whereas men owned bows, arrows, canoes, and tools. If any of these goods ceased to be useful, they would generally be given away to someone who could use them. Theft was rare, because there was no need or context for such an act.

Europeans, on the other hand, loved property and organized their lives around it, and since it held no sacred associations, the General Court (i.e., government) oversaw land transfers to individual or corporate owners. We can easily see the conflict here in the “exchange” of land between Europeans and Native Americans. The latter thought that they were essentially granting gifts of access to the land they occupied to the former—which is why many areas were “sold” to Europeans several times over—whereas the former thought that they were buying up land that they would own in perpetuity at ridiculously cheap prices.

By the time the Native Americans began to understand the philosophical differences that informed what was happening, it was too late. The epistemology of the colonizers and the mechanisms used to enforce it had already redefined the landscape under its own terms. From now on, the owners of this land could forbid trespassing, by force if necessary, with the full power of the government standing behind them. And since Native Americans did not technically claim ownership over any single piece of land, the Europeans could use the Doctrine of Discovery to justify the taking of the land. In fact, this doctrine continues to be upheld today under ten elements defined by the United States Supreme Court, by virtue of a unanimous decision in the 1823 case of Johnson v. McIntosh.

These different conceptions of property can be seen in the very way that the two groups named their landscape. Whereas the English generally used arbitrary place-names that either harkened back to places in their homeland or named the (new) owners of a property, Native Americans identified places according to how the land could be used. What kind of place-names can you find in Westborough today? How do they fit into this naming pattern?

The philosophical differences held by Native Americans and Europeans regarding property and property rights had real world consequences. The European division of the land into individual units that could be measured, bought, and sold reflected a different kind of land use from that of Native Americans. English use of land under this framework had devastating consequences both for Native American life and for the ecology in New England. We will look more closely at these consequences next month.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Works Consulted:

- People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts by Curtiss R. Hoffman.

- The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanityby David Graeber and David Wengrow.

- Second Treatise of Government by John Locke.

- Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North Americaby Pekka Hämäläinen.

- “Borders and Borderlands” by Juliana Barr, in Why You Can’t Teach United States History without American Indians, ed. Susan Sleeper-Smith, et. al.

- “The Doctrine of Discovery, Manifest Destiny, and American Indians” by Robert J. Miller, in Why You Can’t Teach United States History without American Indians, ed. Susan Sleeper-Smith, et. al.

- Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New Englandby William Cronon.

- “A Brief Look at Nipmuc History”by Cheryll Toney Holley, in Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England, ed. Siobhan Senier.

* * *

Take the “Wicked Westborough: Crime, Murder and Mayhem” Tour

Back this year is the “Wicked Westborough: Crime, Murder, and Mayhem” tour, which will take place on Thursday, October 5 from 6:00-8:00 p.m. Join us for a twilight walking tour of downtown Westborough where we will visit scenes of crime, murder, and mayhem that took place in our town. Wander the streets as you hear tales of Westborough’s seedy underbelly, with a cast of criminals and events that are sure to put a chill down your spine.

Due to the nature of the content and the walking distance, attendance is limited to young adults and older. Attendees should wear comfortable shoes and bring a flashlight. This event is co-sponsored by the Westborough Center for History and Culture in the Westborough Public Library, the Westborough Historical Society, and Leduc Art & Antiques, LLC.

Pre-registration for this highly popular event is required. Registration for this event opens Thursday, September 21 at 9:00 AM.

* * *

Hassanamisco Indian Fair and Powwow

The Hassanamisco Indian Fair and Powwow will take place on Monday, October 9 from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. with a Grand Entry at noon. The event will take place at 80 Brigham Hill Road in Grafton and is open to the public.

* * *

September Nature Notes

According to Nature Notes writer Annie Reid, it’s mushroom season! Reid tells us how to find them, but be careful: most mushrooms are not edible, so unless you really know what you are doing, don’t eat them!

Find out more about mushrooms and other seasonal features of Westborough in September’s Nature Notes.

* * *

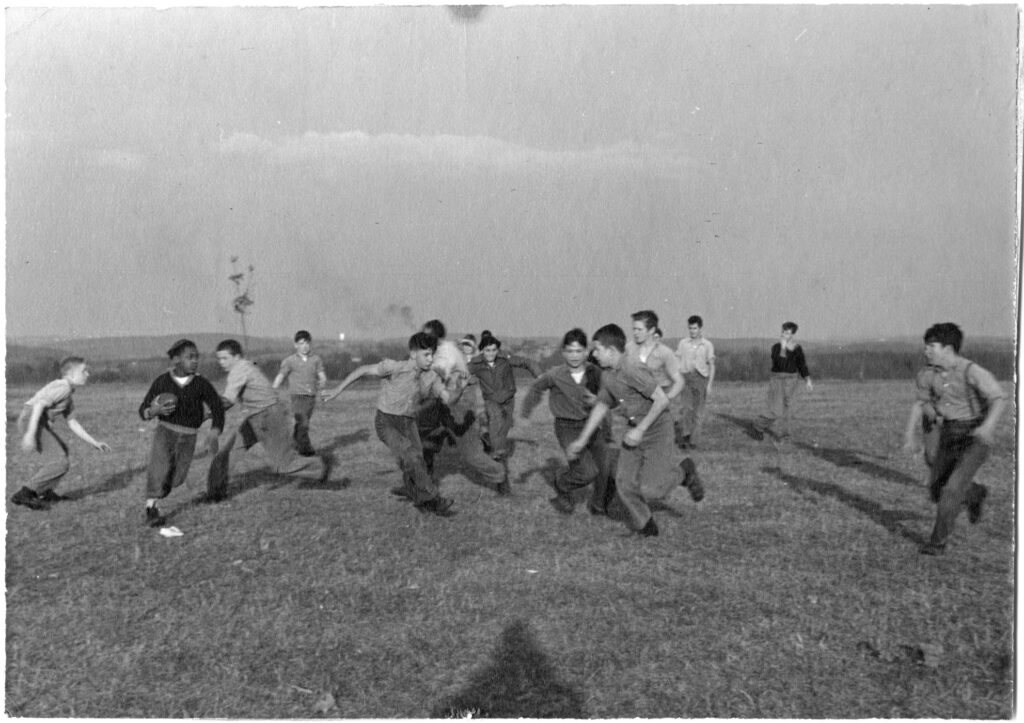

Westborough Football!!!

Stop by the Westborough Center to see the new mini-exhibit on Westborough football through history. See pictures of football players, band members, and cheerleaders from 1903 through to 2018, plus a cartoon celebrating Westborough winning the state championship in 1943.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.