This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

The Hassanamisco Band of Nipmucs Today and Some Reflections on the Series

In 1976, the Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts officially recognized the Hassanamisco Band of Nipmucs. A few years later, the Chair of the Commission and Nipmuc tribal sachem, Zara Ciscoe Brough, spearheaded an idea to create a self-sufficient Indian community on land that was once home to the Grafton State Hospital and that partly crossed over into Westborough. The goal was to put in place “a self-supporting farming community for local Indians” that would include crops, cattle, and gardens, along with the means to offer food and shelter to transient Indians. Settlement plans also included social and cultural activities for Indians and non-Indians alike, and residences would be made available for members of the Nipmuc or any other Indian tribe.

Local Indian leaders originally hoped to receive 500 acres of hospital land to house 400 Indians in an agrarian village. But after the state deeded much of the property to Tufts University to create a veterinary school, they lowered their sights to “whatever the state will give us.” In the end, the Nipmuc Indians, who at one time had lived on this land for thousands of years, did not receive any of this land from the state to help benefit their community. Before the land was deeded to Tufts, it was under consideration to house a 150-bed medium-security prison until heavy push-back by local residents prevented this plan from moving forward.

After securing state recognition, in 1980 the Hassanamisco Band of Nipmucs began to seek federal recognition, but in 2004 their federal application was denied. The main basis for the denial rested on the conclusions of John M. Earle’s 1861 race-based survey of Native American tribes in Massachusetts: because the Nipmucs had historically been grouped together geographically with African-Americans, mainly in Worcester, for reasons that had to do with class and race throughout the nineteenth century, inevitable intermarriage between the two groups disqualified the Nipmuc from constituting a cohesive tribe. So even in the twenty-first century, the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs continued to uphold race, rather than tribal and familial tradition, as the overriding standard to meet for tribal recognition. Ultimately, the traditionally open and welcoming culture of Native Americans undermined their petition in favor of outdated, nineteenth-century European conceptions that prioritized race as the main means for categorizing human beings.

Indians did not simply fade away and disappear once Europeans landed on their shores. Indeed, in his recent book, Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America, Pekka Hämäläinen reminds us that the Native American people controlled much of North America up until the late 19th century. Even though the Hassanamisco Reservation in Grafton occupies a mere three acres, the land itself is unique to Massachusetts in that it has never been owned or occupied by non-native people and has been owned solely by the Nipmuc tribe over the past 400 years of European presence. Today, the website of the Hassanamisco Band of Nipmucs says that they have nearly 600 members, all of whom work hard “to preserve and promote their culture, language, and values,” despite all of the obstacles that were, and continue to be, placed in front of them. In their practice of resilience, they are following the tradition of their ancestors, who also struggled to maintain their identity and connection to their land after the first arrival of Europeans.

Conclusions and Reflections on this Series

I often argue that when we look back in history, we cannot and should not assume that the people who lived back then think like we do today. We have to try to put ourselves in their mindset and let go of ours if we truly want to understand their culture and times. Giving up our current ideological and political frameworks and trying to adopt the ones that were in play during the time and place that is in question is one of the most difficult, but necessary, steps when doing history. At the same time, we have to recognize that the people back then were, well, people, people who sometimes held contradictory beliefs and often disagreed with one another, both between and even within coherent groups—just like today. We have to be willing to recognize the complexity of the human experience and be willing to face that complexity when we look back in history.

If we want to go beyond tired stereotypes about Native Americans and view them as people rather than as caricatures, we have to be willing to see them in all of their complexity. Even though Native American culture values community and promotes peaceful understanding, this same culture also has had people who disagree and sometimes even fight with one another. Native Americans have at times acted nobly, and at others times pettily, just like everyone else in the world. They have revered the environment in which they live, but they have also committed acts that were destructive to it, such as overhunting the giant mammals of North America thousands of years ago or, more recently, the beaver in response to European market demands. But if we are going to embrace learning about Native Americans and all of their complexity, we also have to be willing to apply this same framework to the settlers who encroached on Native land by seeking to understand their contradictions and complexity. In other words, holding up either group as an embodiment of a transcendent moral standard in order to score political points today is doomed to failure in the face of historical accuracy.

Researching and writing about the meeting of Native American and European cultures has made me a better person. Learning how the worldviews of both groups shaped their lifestyles, decision-making, and interactions has helped me to understand more precisely the many ways that human beings can come together and organize themselves. I find a lot about Native American epistemology and philosophy—much of which was new to me before I started researching and writing this series—to be appealing. And I wonder what would have happened if Europeans had arrived in North America with more curious minds rather than with avarice and insularity guiding their actions. What if Europeans came to America with a realistic expectation of living side-by-side with Native people, rather than claiming the “open and unoccupied” land as their own, and if both groups were able to use their varied knowledge and experiences to improve all of their living situations in North America? What would that result have looked like? Unfortunately, we cannot turn back the clock and change what happened in the past, but we can learn from the past and then try to adopt what we like and avoid or change what we do not.

I often say that asking the question of what it means to be American is one of the most American things that we do. Unlike older countries and cultures that have long traditions, our American culture and society is in a constant process of “becoming,” which is what makes our country so dynamic and exciting. But even as we begin to see how Native Americans have influenced American society and culture more than we normally have given them credit, Native American history still forces us to confront the question of what it means to be American in uncomfortable ways. Today, we celebrate the great diversity of people in our country, but that diversity was enabled by taking land from Native Americans to create, in essence, a new space where people can find refuge and opportunity from every part of the world. The cultural dynamism that we now enjoy was built on the sins that Europeans perpetrated on Native Americans starting when they first arrived in North America. But Native Americans and their history can also guide us into realizing and defining what it truly and uniquely means to be an American.

My hope is that this series serves as a beginning for exploring Native American history on its own terms within the context of Westborough history. I am not a traditional historian, so there are many details about this history that I left unexplored. What is clear, however, is that when we talk about Westborough history, we must start with Nipmuc history. And once we go down that path, we more clearly see how four migration patterns, each one tied to a specific economic practice or development, have shaped Westborough and its people over time.

The first group to inhabit the area where we live were Native Americans, who arrived here eight to ten thousand years ago as hunter-gatherers and who at some point also engaged in polyculture planting, an agricultural practice that works closely with native plants and the natural environment to optimize food production. The second migration wave was the English starting in the 17th century and proceeding through much of the 18th century. This migration pattern brought European agriculture to the “New World” where domesticated animals helped clear the land for monoculture planting (that is, single crops planted on individual fields) of both native and European-imported crops. The third migration took place in the 19th century, when Irish and French-Canadians came to Westborough to work in the factories that sprung up after a railroad was built through the center of town. And today as part of the fourth migration, people from South Asia and other parts of that continent are moving to Westborough to work in the technology and medical industries in our region.

What makes living in Westborough so interesting is that the history of these four migration periods are still visible to us and that we continue to tell stories about them to each other. To this end, we owe it to ourselves and to history to tell a more accurate narrative about Native American life in Westborough than we have up until now. We do not need to rely on tales with dubious origins to tell the “Native American story of Westborough.” We can instead read Curtiss R. Hoffman’s book about his archaeological studies of the Nipmuc Indians; look closely and critically at the land grants that were used to justify taking away and limiting Native American access to the very land where they used to live; and turn to Rev. Ebenezer Parkman’s diary and similar resources for more reliable insight into how early members of our town continued to interact with Native Americans throughout the Colonial Period, all the while keeping in mind that these accounts come from the perspective of a Congregational minister.

Even better, we can investigate projects that seek to recover early Nipmuc history, such as the Reclaiming Heritage: Digitizing Early Nipmuc Histories from Colonial Documents, a joint project between members of the Nipmuc community and the American Antiquarian Society. Or we can look for ways to interact with the Hassanamisco Band of Nipmucs today, such as attending one of their Powwows. When we engage in consulting these kinds of resources, the history that results is far more interesting and connects much more to our lives today than continuing to tell a rote package of nineteenth-century “Native American” stories about Westborough, stories that minimize the complexity of Native American culture and experience and ultimately serve to valorize European presence on the land where we live today.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Works Consulted:

- “A Brief Look at Nipmuc History” by Cheryll Toney Holley, in Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England, ed. Siobhan Senier.

- “Indians Eye Hospital Land” by Robert P. Connolly, in The Evening Gazette, March 17, 1979, pp. 21-22.

- Report to the Governor and Council concerning the Indians of the Commonwealth, Under the Acts of April 16, 1859 by John Milton Earle.

- “Massachusetts Nipmucs and the Long Shadow of John Milton Earle” by Christopher J. Thee, in The New England Quarterly, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Dec., 2006), pp. 636-654.

- “Peoples of Agency or Victim-hood?: Africans and Indians” by Peter Feinman in State of New York State History (blog) for the Institute of History, Archaeology, and Education.

- “National American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month” in National Register of Historic Places (website): https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/national-american-indian-and-alaska-native-heritage-month.htm.

- Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America by Pekka Hämäläinen.

- The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow.

- People of the Fresh Water Lake: A Prehistory of Westborough, Massachusetts by Curtiss R. Hoffman.

* * *

See the New Exhibit on The Round Table

Stop by the library to check out a new exhibit on The Round Table, a literary and social club that began in the nineteenth century in Westborough and lasted for well over one hundred years. The club met on a regular basis throughout each year at member homes to learn about and discuss a host of topics, including literature, politics, culture, and social concerns. The club even ventured into holding theatrical events and gathered outdoors for picnics during warmer months. The exhibit is in the display case in front of the Westborough Center and includes programs and pictures at various points in the club’s history.

* * *

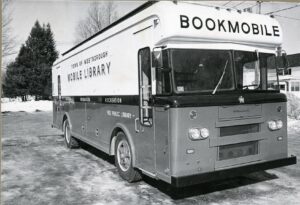

The Digitization of Westborough’s Historical Photographs Are Headed to Completion

Since arriving in my position as the Local History Librarian here in the Westborough Public Library, I have periodically been engaged in digitizing our Historical Photographs, but the sheer size of the collection has meant that I have only been able to make limited headway into completing the project.

Now, thanks to an unexpected windfall of grant money from the Internet Archive and its Community Webs program to fund digitization activities, we have decided to send both our Historical Photographs and our Historical Postcard collections out to a vendor to complete the digitization of these collections. During the time when they are away, these collections will, of course, be unavailable, except for a sizeable number of images that I had already digitized and put online in the Westborough Digital Repository. But once the digitization of these collections is completed at some point in the spring, everyone will have free and easy access to all of these historic images through their computers.

* * *

A Valentine’s Day Visitor?

Did Pepé Le Pew pay you a visit on Valentine’s Day this past week looking for some love from you—or from that of your cat? Okay, maybe Pepé Le Pew himself did not make a guest appearance on your doorstep. But such a visit by another skunk would not have been entirely implausible, says Annie Reid in one of her past Nature Notes essays, given that skunks come out for mating season around mid-February.

Learn what other wildlife you should look out for this month in Reid’s Nature Notes for February.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.