Author: Samuel Edwards; MA SHRAB Archival Field Fellow

My placement through the State Historic Records Advisory Board was with the Saint Peter/San Pedro Episcopal Church in Salem. Founded in 1733, the church is one of the oldest in Salem, and one of the earliest Episcopal churches in the United States overall. They also house the oldest church bell in the United States, and have the oldest cathedral. As I entered into the beautiful and imposing historic church, Reverend Ives, the church rector, told me stories of how the founder was persecuted during the Salem Witch Trials and how the church closed shortly after the Revolutionary War when windows were broken and parishioners spit upon by supporters of the Revolution who were opposed to the Anglican church due to its ties to England. St. Peter’s buzzes with history and fascinating stories, and after this project, we will be able to unearth even more.

St. Peter’s/San Pedro Episcopal Church viewed from the street

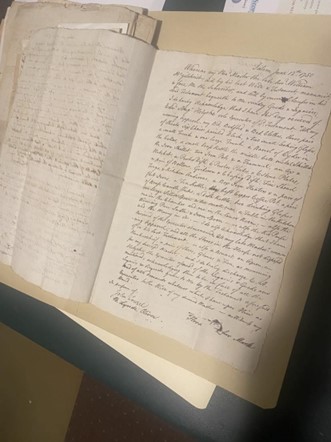

Not all of those stories are triumphant, however. While researching their history, the church discovered that some early reverends of the church were enslavers. The church is currently in a process of confessing their historic complicity in the slave trade and working on material reparations for African Americans in their community. Making their earliest records accessible and accessible for research is part of that process, allowing the church to better understand their history. We know from records that Reverend McGilchrist (1747-1774) enslaved a woman named Flora, and granted her freedom and several small items in his will. During this process, we discovered a document with Flora’s mark where she recorded the items that he willed to her.

The document mentioned above, showing Flora’s mark.

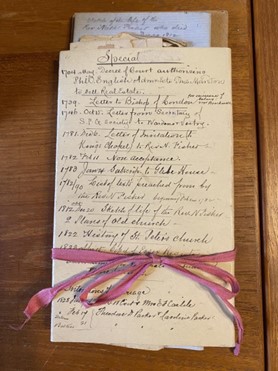

The collection itself was in a unique situation as it had been previously transferred to the Peabody Essex Institute around 1968. However, the church made the decision to reacquire their historic records in 2022, in order to make these records more accessible to their staff and parishioners as they do this vital research work into the history of slavery in relation to the church. Due to the previous archival processing, much of the collection was in decent shape, but there were three boxes that were still a mystery to the church. These boxes had “packets” of documents that had been tied up with string, folded in on themselves. The packets had material dating from 1705 all the way to the 1940s, although the majority of the materials were from 1733-1892. These were the boxes that I would focus on for my fellowship.

Typical packet of documents as I found them.

I began by creating an inventory of the packets, which was relatively simple as many of them were labeled already by a previous archivist. After that, I began the process of flattening and refoldering all the materials, and quickly found that the collection was much larger than I had previously assumed. Some packets ended up being 12 folders! What started as three boxes became seven. These packets were a hodgepodge of letters, financial records, sermons, and administrative records. I even found one small prayer book that was owned by Reverend Fisher, who served at the church from 1782-1812. Handling these handwritten manuscripts provided a direct line to the past, as I imagined them being faithfully written out with love and care in this very church.

Kick-off day at St. Peter’s when the project began.

Working with this collection was supremely gratifying to me, particularly as so many of the records overlapped with history before the “United States” as we know it even existed. Through this project, I learned a great deal about Massachusetts history, the history of slavery in New England, the history of the Episcopalian church, and the history of Loyalists during the Revolutionary War. Thank you to Reverend Nathan Ives, Jill Christiansen, and Roving Archivist Thomas Doyle for all your help and for making this project possible.