By Brian Boyles

This article was originally published in The Relentless Humanities, a newsletter written by Brian Boyles. Subscribe here.

Vessels of Slavery is on display at the Cape Ann Museum’s CAM Green Campus through Sept. 1.

The clatter of lines against a mast, the wood groaning in the wind, a gull’s cry. These are the sweet sounds of the New England coastline in the summer. Like generations of men who’ve called this place home, I look up at a sail spread out against a blue sky.

My feet are not on the deck of a boat nor on a dock, but firmly planted on green grass. The sails before me and behind me are works of art, carrying me not across a harbor, but towards knowledge of the land around me.

The last wisps of Hurricane Debby passed in the morning, just in time for the Cape Ann Museum to welcome people to its CAM Green campus for the opening of Vessels of Slavery: Forget Me Not. The Saturday afternoon event is two years in the making; centuries, really.

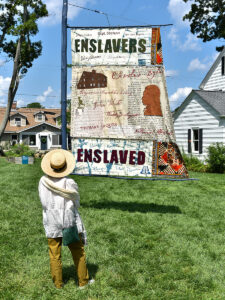

Created by the artists IlaSahai Prouty, Susi Ryan, and Christle Rawlins-Jackson, Vessels of Slavery consists of the six sails attached to wooden poles painted blue, a wooden boat draped with a quilt and three Engungun panels positioned around the green. Each sail stands more than ten feet tall. Today, people gather in groups or drift from sail to sail, pausing to look at the designs and words stitched into the sails. It is hot, and other visitors hug the shade along the walls of CAM’s Janet & William Ellery James Center.

What we experience today is evidence of what is possible when artists and institutions choose to study the legacy of enslavement with a commitment to courage and openness. That commitment is available to each of us, should we choose to take the journey. Indeed, Vessels of Slavery shows why that difficult work enriches the places where we live.

Prouty is originally from Gloucester and now an Associate Professor in the Department of Art at Appalachian State University. Ryan and Rawlins-Jackson are members of Sisters in Stitches: Joined by the Cloth, a quilting collective that continues to gain acclaim in Massachusetts and beyond. I first met Ryan when she contributed to We Too Are America, the first anthology of essays by Clemente Course in the Humanities students published by Mass Humanities in 2020. A graduate of the Clemente Course in Worcester, Ryan wrote about her quiltwork and the inspiration of her ancestor, Venture Smith, a member of the Dukandarr tribe in Gunea, who was captured and enslaved. After purchasing his freedom, he shared is story in The Narrative of the Life and Advntuers of Venture, published in 1798.

“Following in the footsteps of my ancestor,” wrote Ryan, “I too continuosly seek liberty, justice and equality for all through hard work and storytelling. So much of my memory is carried through cloth, and cloth has given me voice.”

Their creative process was a powerful intermingling of the humanities and artistic practice, supported by Miranda Aisling, Head of Education & Engagement at CAM and a rising star in the Massachusetts musem world. In four week-long residencies a the Manship Artist Residency, Prouty, Ryan and Rawlins-Jackson conducted research in the Cape Ann Museum Library and Archives and other repositories. Scholarship exists on the history of enslavement in the region, and the artists recall being told, “This research has already been done. You will not find anything new. Please refer to our work.” Their insistence on diving into the archives was, itself, a form of resistance and a central factor in the art they created.

“Whether we found anything ‘new’ or not,” write Prouty, Ryan and Rawnlins-Jackson, “our goal was to look with our own eyes, to touch the documents with our hands, to witness, and to bring our perspective to bear.”

At the same time, they invited community members and local institutions into conversations about the history and people they sought to honor. The conversations made space for grief and celebration as they acknowledged and honored ancestors who were enslaved and freed.

Among the partners for these conversations was the Wellspring House in West Gloucester, a nonprofit that provides housing, education, job training, and career readiness to North Shore resdients. Like the Cape Ann Museum, Wellspring was supported by an Expand Massachusetts Stories grant from Mass Humanities. A team of Wellspring staff and humanities scholars researched the history of the Freeman family, a prominent Black family that for over 100 years owned the house where Wellspring is headquartered today.

As Aisling noted at the Vessels of Slavery opening, there is remarkable momentum across Massachusetts to reckon with the past through humanities projects that place community members in the positions of power and direction. The field is a crossroads for storytelling conducted at traditional humanities organizations like museums and in spaces with different missions but the same commitment to truth-seeking.

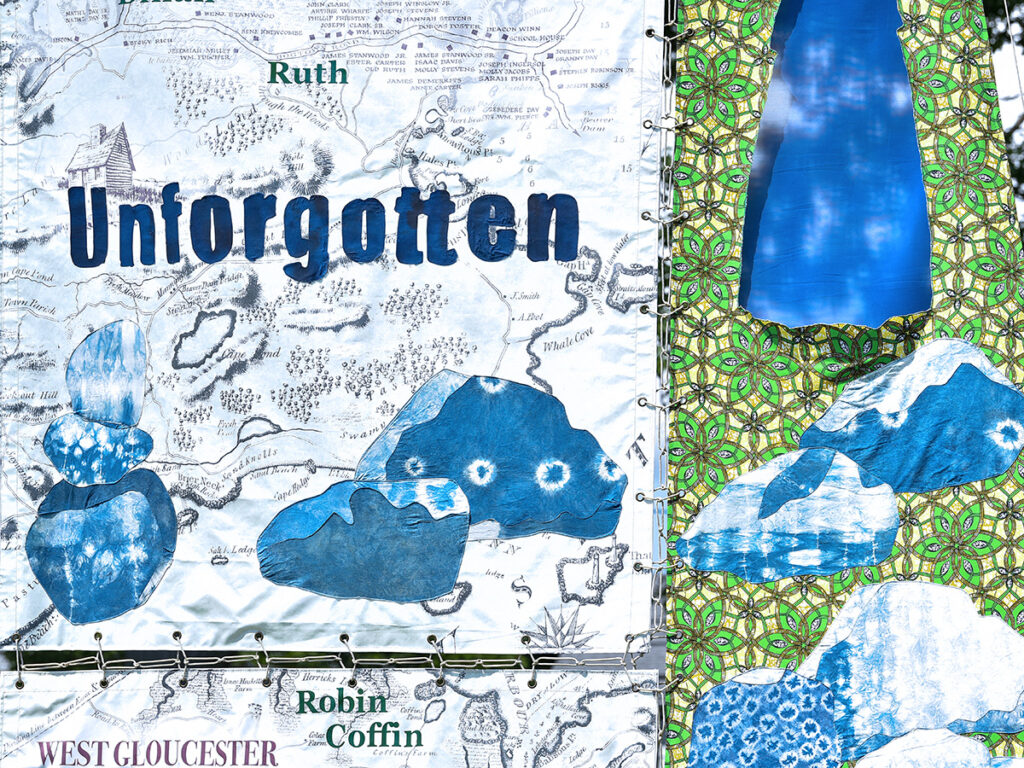

Together, the artists created six sail-quilts, each with a theme that they stitched in block letters: Enslaver Enslaved; Stolen Wealth; Forget Me Not; Unforgotten; Persist, the Work Carries On and Freeman.

Enslaver Enslaved bears the names of individuals known to be enslavers and the names of those they enslaved, including people of African descent and Indigenous people. The artists’ research included learning that the two houses at the other end of the green were sites of enslavement. From the program guide: “The house featured in the upper left corner of this sail is the White-Ellery House (1710), which sits on the southeast corner of this property. Primm, ‘an Indian lad,’ lived in this house and was owned by Reverend John White.”

Seeing the names of enslavers and enslaved brings us back to the cold facts of that society while asking us to imagine them as humans. Right there, not thirty yards from the sail, is a building that held captives.

Stolen Wealth reminds us that slavery was an all encompassing system, one that involved almost every aspect of America’s economy. Cape Ann was both the site of enslavement and a cog in that wheel, providing supplies to plantations in the Caribbean and South America.

“Fisherman from Cape Ann played a vital role as their salted cod was shipped to various places to feed those enslaved,” reads the program guide. “Slavery was the root of capitalism in America.”

From the house across from the museum building, the members of the Akwaabaa Ensemble emerge and slowly dance towards a group of drums and xylophones fanned out in front of the audience. Akwaabaa translates as ‘welcome‘ in the Akan language. The group’s leader, Theophilus Nii Martey, introduces a song written for Ghanian independence. The music is as bright as the day, and despite the heat, Akwaaba gets the audience on their feet. Now the crowd moves into a circle, now the three quilt makers join that circle. Now it is a group of people honoring and uplifiting the stories on the sails. Now it feels like a community.

When we think of Cape Ann and Gloucester, we think of fishermen—sturdy, white men. That image travels beyond Massachusetts in narratives like A Perfect Storm or the television show “Wild Tuna.” Gloucester is a gorgeous town, well-preserved, with friendly people and many different types of beaches.

Vessels of Slavery complicates that history, but it takes nothing away from the historical importance of this place. When we commit to reopening the archives and reimagining the past, we do not put our homes and heritage at risk. Instead, we address the risk that some of our neighbors feel, that unwelcoming exclusion, that erasure. We do better when we refuse to settle for the ossified past. The humanities reset the terms for the present and future.

The next day, my family takes a 2-hour trip on Adventure, a schooner that operates as a living monument to Massachusetts’ fishing heritage. Built in 1926 and retired from fishing in 1954, the boat had broad sails, a great crew, and a captain, Christa Miller-Shelley, who answers my nautical and historical knowledge with ease. She mentions that Gloucester’s original fishing industry grew with boats like this, which were part of the trade in saltfish.

The sun starts to set. I look at the coastline at the golden hour, see my children watching the sails come down. The world around them dazzles, the water and the friendly people and all that beautiful land on either side of us. And I think about saltfish, that some part of the wealth and bounty surrounding us came courtesy of violence and tragedy.

And this knowledge did not make my time on the boat less beautiful. It made me want to explain the world to my children honestly. It reminded me how deeply we depend on those artists, scholars, musicians, and museums who are unafraid to raise a different set of sails.