Thinking Historically Is Hard to Do

While talking with my two daughters, sometimes I feel like we come from entirely different worlds.

Such a difference may be understandable: they mainly grew up with digital technology forming the very basis of their social lives, whereas I grew up having to wait in line to use the one available phone in my home if I wanted to connect with a friend. But the difference between us goes beyond me not knowing the latest trending TikTok video, or emoji, or technology term. Their entire frame of reference to the world seems to be different than mine. And if this huge difference between us came about in less than one generation, how much difference must there be in the way we see the world now from those who lived in the past?!

Many people believe that the practice of history entails compiling lists of dates, lists of important people, and lists of important events and then tying the information in these lists together into some kind of cohesive story that accounts for as many of these facts as possible. Sure, history can be written in this way, but the result would be rather dull. (Unfortunately, many high school textbooks meet and never exceed this low bar!)

Simply knowing who wrote the Declaration of Independence, what it contained, and who signed it on July 4, 1776 is not interesting history. But the event itself raises all kinds of interesting questions: Why did Americans feel the need to make such a declaration? Who authorized this group of people to do so, and how did this authorization come about? Why was Thomas Jefferson enlisted to write it? What did the signers hope to accomplish? Did they reach consensus easily, or was deliberation on its contents fraught with tension? What was the source of any tensions? In order to answer these more interesting questions we need to go well beyond our simple lists of dates, people, and events.

But answering these kinds of questions is complicated. We need to seek out other kinds of evidence: diaries, letters, newspapers, etc. All of these resources involve different individuals with different backgrounds and agendas presenting their take on a given event. Historians then must sift through all of this evidence, make inferences, and come to some kind of conclusion as to what all of it means. Needless to say, their interpretations will necessarily be open to revision as new sources of evidence come to light and as new ways to consider all the evidence emerge. Suddenly, we do not seem to be in the realm of facts any more—at least not in the way that we thought about facts at the beginning of this process of practicing history.

What I have just described, however, is not even the reason why thinking historically is so hard to do. The greatest challenge to practicing history is our tendency to use the present as the natural anchor from which to see and judge the waves of history. To think historically, we need to lift this anchor and give ourselves the freedom to ride these waves and be open to trying to understand how people thought, perceived, and acted differently than we do now. To believe that all people throughout all of history are pretty much just like us—they only had to deal with a different set of facts—is to miss out on the entire point, and the joy, of doing history.

We think about the world differently than people from the past did. Many of the thoughts and ideas that we take for granted today were not available to those living in the past, so many of our contemporary thoughts were, well, unthinkable to them. At the same token, many of the thoughts that they had are in a way unthinkable to us, because they don’t make sense in the context of our modern world. I am reminded of the scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail of the peasants digging in the mud and discussing Marxist theory. What mainly makes the scene so funny, of course, is that such ideas would have been impossible for such peasants to think at the time.

If we truly want to understand the past, we have to do our best to place ourselves in the mindset of the people who lived during the given time and place that we are studying. It means immersing ourselves in the social and cultural artificats that these people left behind and then using them to try to think like they did. And it means giving up the notion that the people who lived before us are simply earlier versions of ourselves. And that’s hard to do!

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Selected Reading:

* * *

Harriet Merrifield Forbes Photo Album

I recently digitized a photo album of cyanotypes taken by Harriet Merrifield Forbes that belongs to the Westborough Historical Society, and you can now see them here: https://westboroughdigitalrepository.omeka.net/items/show/1133 (To see the photo album in order, scroll down to the bottom of the page of each image and click on “Next Item.”)

Forbes often wrote about Westborough history, most notably in her 1889 book, The Hundredth Town, Glimpses of Life in Westborough, 1717-1817. She took the cyanotypes sometime around 1894. A cyanotype is created through a photographic printing process that creates cyan-blue prints from photographic negatives. The advantage of such a process is that it is relatively easy to do and was a popular way to make prints around the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Recently, the practice of creating cyanotypes has seen a resurgence by artists interested in exploring what this process can do for their photography.

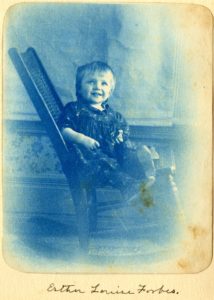

One of the images from the album is of a young Esther Forbes, who was born in Westborough and went on to win both the Pulitzer Prize for Paul Revere and the World He Lived In and a Newbery Award for Johnny Tremain: A Story of Boston in Revolt. But there are also many pictures in the album of buildings in and around Westborough.

* * *

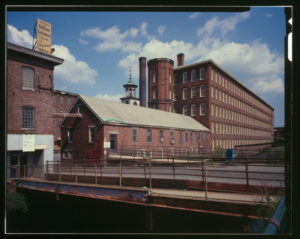

Industrial History of New England

The industrial history of New England is fascinating, and Westborough played a role in it during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. I recently discovered a relatively new website devoted to the topic: https://industrialhistorynewengland.org/. Right now, the site mainly lists museums and other historical sites where you can learn about this history. Put visiting one of them on your list of things to do as we slowly move into spring!

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Local History Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.