May 13, 2022

In object-based research, it is sometimes just as important to examine what is not shown as it is to observe and analyze the visible features of an object. I think of this as examining the “negative space” of a piece of material culture. The stories illuminate the object if we look at it anew. Mary Fleet’s needlework picture can be read in terms of what it displays, but does not show—namely, the enslaved labor that her family’s wealth relied upon.

Mary’s work

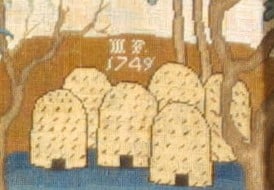

In 1749, twenty-year-old Mary Fleet stitched this fascinating needlework picture. At that time, needlework was a core part of elite young women’s education. It trained them in morals, aesthetics, and practical skills seen as appropriate for young women of their social class. However, their needlework did not only represent lessons learned. This kind of decorative work was also a display object—an advertisement, even. Mary’s needlework shows the wealth and status of her family and was put on display to celebrate that fact. The Fleet family showed that they could afford to give their daughter the time and resources to make this time-consuming, laborious piece of decorative work. This piece was the culmination of years of careful (and expensive) needlework instruction, as evidenced by at least two other extant pieces of needlework that Mary stitched as a teenager.

Mary’s father, Thomas Fleet, was a renowned publisher and newspaper man in Boston. Over the course of his career, he published the Boston Evening Post, pamphlets, ballads, and an array of other print media (including his compilation of Mother Goose’s Melodies). Fleet acquired wealth that he put back into his business and into his children’s education—that was on display in Mary’s work. Nevertheless, that wealth fundamentally relied upon the labor of enslaved people, several of whom worked in Fleet’s print shop. Mary’s leisure time and resources cannot be understood outside this context and neither can the imagery in her needlework.

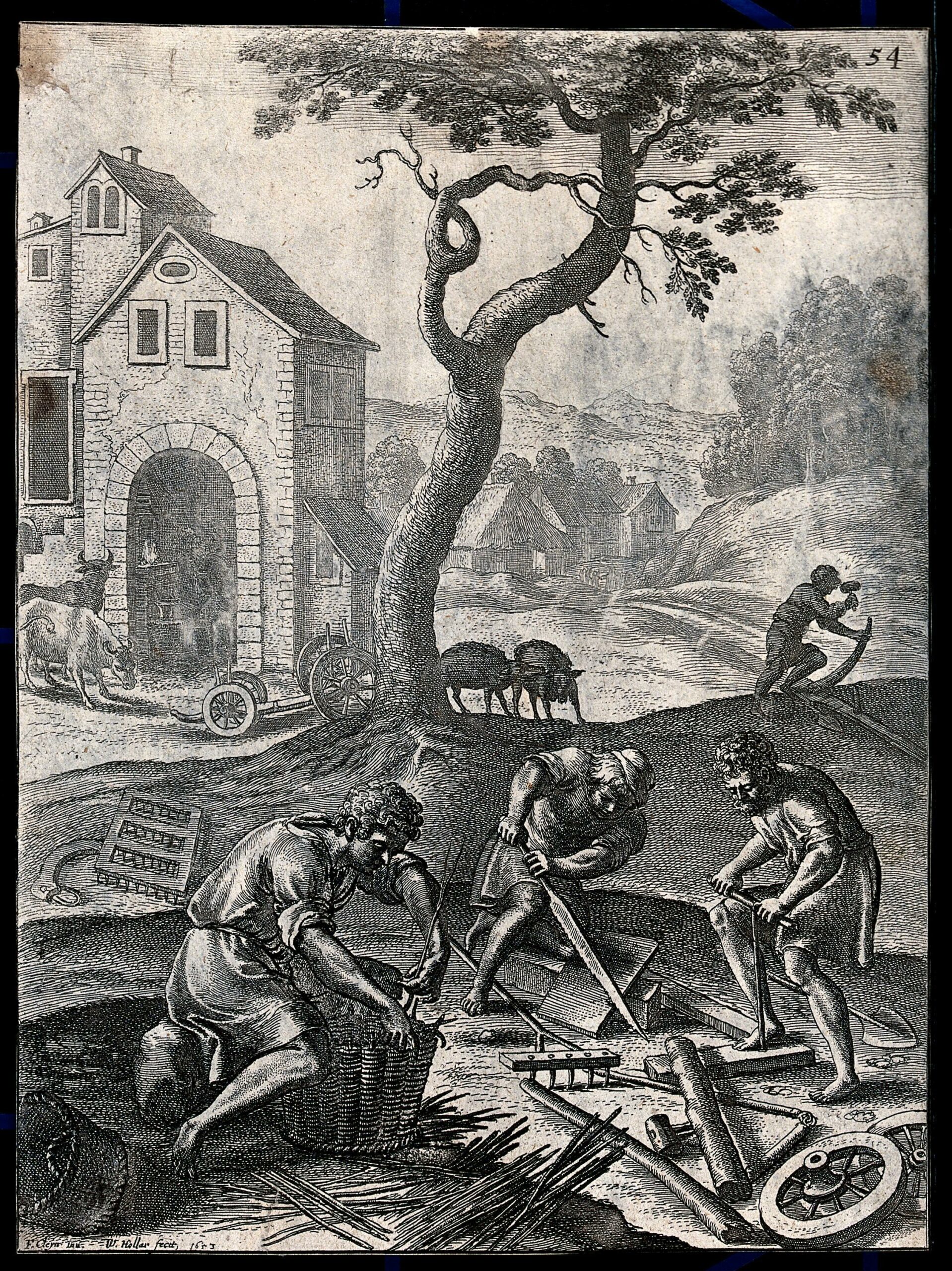

Mary Fleet’s needlework is all about work. It depicts scenes from Virgil’s Georgics, as discussed in Historic New England Senior Curator Nancy Carlisle’s essay in Cherished Possessions. Virgil’s poem is a meditation on agriculture written in Latin in 29 B.C.E. It was a popular work, inspiring a whole genre. Bostonians at this time often idealized depictions of white, male agricultural and artisanal work.

Mary’s needlework picture is a composite of at least three separate illustrations that accompanied printings of the lengthy poem [1]. As her father owned a print shop, Mary would have had access to a wide array of print sources and her needlework shows that off. It advertised her familiarity with classical texts and her access to print materials, as well as her family’s wealth and her skill. But it also made a new scene from existing materials, collapsing three busy scenes into a much quieter one.

While the etchings on which she based her needlework show many people working, Mary’s stitching features a lone basketmaker. It shows a popular image at the time: a romanticized connection between an individual maker and nature. Scenes of many hands at work become an image of one. We can read this in the context of her father’s work, which relied on but also rarely acknowledged the presence of other hands.

Many hands in the print shop

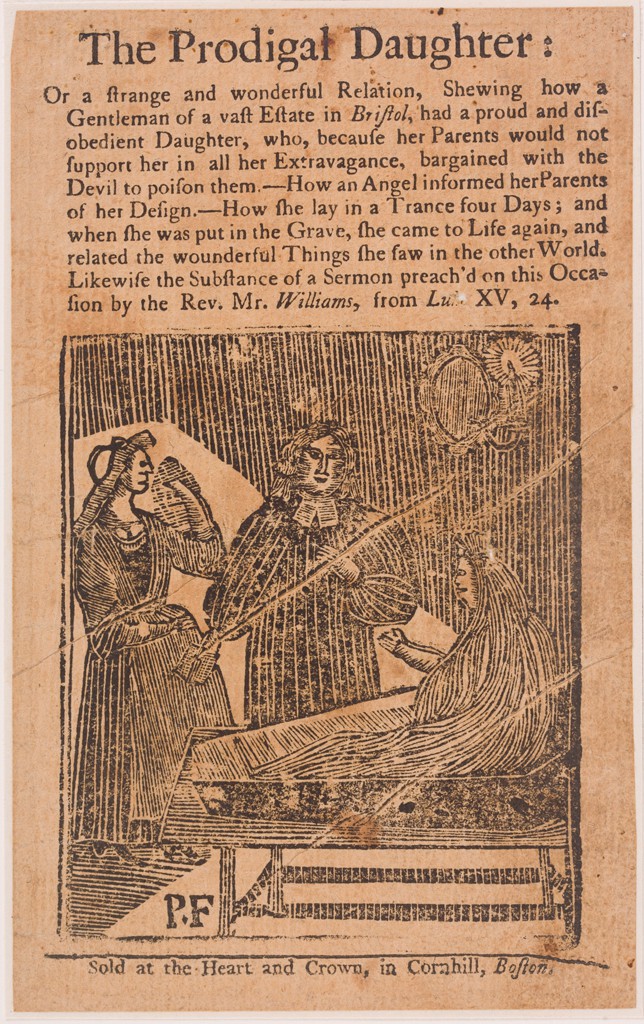

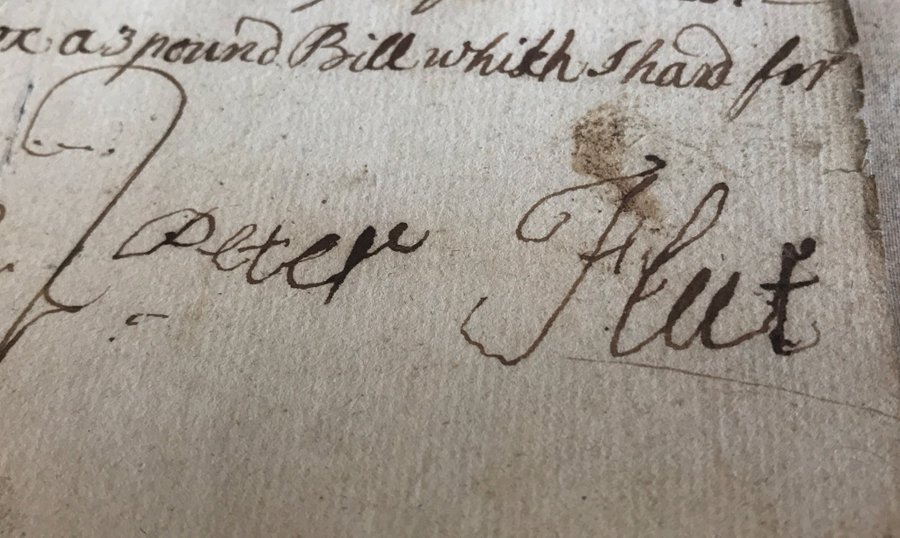

However, many hands did contribute to the work done at Thomas Fleet’s print shop at the Heart and Crown in Cornhill, Boston. Specifically, several enslaved people worked at the print shop. Of those people, Peter Fleet is perhaps the best known, though it is challenging to identify much of his work. Peter Fleet, enslaved by Thomas Fleet, was a highly skilled typesetter and printmaker. Isaiah Thomas, another local printer, described him as “an ingenious man [who]… cut, on wooden blocks, all the pictures which decorated the ballads and small books of his master.” [2] Not only did Peter lay out the blocks that spelled out the news that Bostonians consumed, but he also carved the meticulous illustrations for the printing house’s publications. Evidence of his hand abounds. An illustration for a popular publication, The Prodigal Daughter Revived, even bears his initials: “PF” in the lower left-hand corner.

The “PF” in the corner recalls the way Mary later labeled her needlework: “MF” is stitched in the upper right-hand corner. It is worth considering what else Mary observed about Peter Fleet and his work.

Peter’s Will

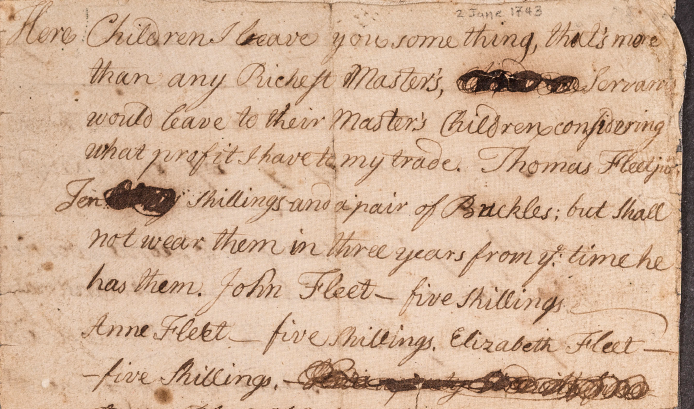

Peter Fleet certainly observed the Fleet children. He left a will that addressed them explicitly. It is a complex, fascinating document. He wrote it in 1743, though he likely lived until 1758. In his will, he directly addressed the surprise that some may have felt in reading such a document:

“Here Children I leave you something, that’s more than any Richest Master’s, [blacked out] Servants would leave to their Master’s Children considering what profit I have to my trade. Thomas Fleet jun Ten [blacked out] shillings and a pair of Buckles; but shall not wear them in three years from ye time he has them…”

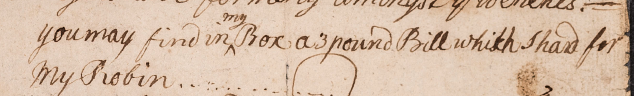

He went on to note that at least three other Fleet children (John, Anne, and Elizabeth) should receive five shillings. Fleet wrote that he came by this money through his own labor (“I would not have you think that I got this money by Rogury in anything… I got it honestly…”) and explained that he had saved up years of tips from delivering newspapers. One of the most important parts of the will, though, is at the very end: “You may find in my box a 3 pound Bill which I had for my Robin…. All that’s left is for Molley & Venis.”

Historians have questioned why an enslaved man might leave money to his enslaver’s children. We will likely never know the answer to that question. But the gift of three pounds is telling. It is six times more than the ten shillings allotted for Thomas Fleet’s eldest son. This was likely for his own child, Robin. And Venus, who was to receive half of “all that’s left,” was a seventeen-year-old woman enslaved in the household. In the end, Peter Fleet carefully worked to provide for those who he might have worried he would be unable to protect once absent. Leaving money for Thomas Fleet’s white children and having them sign as witnesses increased the likelihood that Peter’s wishes would be honored [3]. This will displays his desire to direct the course of his possessions in the future. It may also have been used to try to shape the present.

After allotting several shillings to other Fleet children, he says:

“What little I had thought to give it to Molley; but thought her sister Anne would make a Scuable [sic] and take it from her… There is more than enough, yet, left for Molley, because she is very good to servants… All that’s left is for Molley & Venis”

Mary Fleet was fourteen, two years younger than her sister, Anne, and is almost certainly the daughter referred to. She is the only living Fleet daughter not otherwise mentioned in the will and “Molley” was a common nickname for Mary. Peter Fleet notes that Molley/Mary “is very good to servants.” This is not to absolve Mary Fleet or to suggest that the experience of enslavement in the Fleet household was not cruel. But he took the time to show the Fleet children that he observed their actions and that their behavior towards the people enslaved in the household might not go without consequences (or rewards). Perhaps he hoped to shape their behaviors, to extend some more protection over Venus and Robin after his death. We cannot know his mind. But we can read his words, study the evidence of his hand.

Most of the written sources that document the lives of enslaved people are from the perspectives of their enslavers. It is important to look at those documents with skepticism and a willingness to read between the lines, to see what is going unsaid. But we can also look beyond these direct examples.

Mary’s needlework does not necessarily communicate anything direct about the lives and labor of the people her father (and later, her brother) enslaved. But this depiction idealizes male labor. It portrays a white man creating independently in an agrarian setting, tells us about the image that her family hoped to project. It is important to counter that image and to show the labor that her family’s wealth was truly derived from and to think about what this advertisement of resources meant in the context of the enslavement of several people within the Fleet home and print shop. We are fortunate to have Peter Fleet’s own words and his own mark to help amplify his story. It shows some of the ways he exercised agency within a system that sought to deny his full humanity.

Next Time

In my next blog post, I will share the story of other young people enslaved in Thomas Fleet’s household. I will note how material culture can give us glimpses into the ways they, too, exercised agency and worked to make free lives for themselves. That account will take us from Boston to Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone, looking for a story that emerges between the lines.

[1] Nancy Graves Cabot. “Engravings as Pattern Sources: I, Embroideries of Three Faith Trumbulls.” Magazine Antiques 58:6 (December 1950), pp. 476–479. Nancy Carlisle also discusses this in her essay in Cherished Possessions.

[2] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America, (Published by the Press of Isaiah Thomas, Worcester, MA: 1810), 99.

[3] Justin Pope, “A Slave at the Press: Peter Fleet and Reports of Slave Unrest in the Boston Evening-Post, 1735-1758,” Slavery & Abolition 42, no. 4 (2021): 691-709.

See also Jared Ross Hardesty, Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 157–8.

Mariah Gruner, Ph.D. is the Recentering Collections Curatorial Fellow.

Over the course of her IMLS grant-funded fellowship, Mariah Gruner will work with the collections services team to draft a new collecting plan and develop a body of research that explores marginalized and suppressed stories within Historic New England’s existing collections. Mariah will share monthly updates about the collecting plan and her research.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.