It’s a familiar refrain when it comes to teaching Black history that holidays and heroes are not enough. Black History Month and a few of Martin’s iconic words and images of Rosa is not a comprehensive history. Unfortunately, these approaches are commonplace, making tacked on and Pollyanna efforts the norm in many social studies classrooms.

Much more curricular inclusion, pedagogical relevance, and cultural and policy overhauls have always been needed to transform schools from institutions that, in their own subtle and overt ways, shape and reinforce the inequities of American society.

As protests against racism and racial injustice unfold today, the social imperative to reimagine schooling and enact substantial and lasting reforms are not new but they are acutely pronounced. Addressing structural racism in America is accomplished through institutional change in policing and incarceration but, also, education.

George Floyd died at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer who pinned Floyd’s neck to the ground for over eight minutes while he cried out that he could not breathe. Bystanders pleaded with the officer while cameras rolled. This moment, one that did not have to be Floyd’s last, catalyzed global protests against racial injustice. It is also a reminder of the urgency of turning theory into action when it comes to making schools much more welcoming, responsive, and designed to meet the needs of all students, particularly Black students and those who are underrepresented in curriculum and undervalued in classrooms.

Talk of multicultural education, culturally relevant pedagogy, or critical race theory is only as powerful as the action in engenders. This moment of anguish and grief begot collective action in the streets. It must also redouble the efforts of educators to teach with a social conscience and educate for a critical consciousness.

When thinking about the messages that students receive in schools, we have to remain vigilant of the role this institution plays in shaping collective memory and forming identities. It is a place where society can conceal, forget, and diminish as much as it can reveal, remember, and value. Schools are social crucibles, yet what is actually forged when Black history is under-appreciated and the dominant narratives of American history are uninterrogated? What narratives are we privileging as educators? What narratives are we silencing? What can we do to change this today, tomorrow, and in a sustained way moving forward?

It is the responsibility of every educator to confront curriculum with critical eyes. It is no secret that there are dominant narratives in social studies classrooms that are overly romantic, exclusionary, and acritical. It is well-established that there is a hidden curriculum in schools, elevating certain voices and perspectives while displacing others.

This moment of anguish and grief begot collective action in the streets. It must also redouble the efforts of educators to teach with a social conscience and educate for a critical consciousness.

Schools send implicit messages about who is accomplished, successful, intelligent, and has worth. They also send messages about who is inferior and less noteworthy in their contributions to the saga of human history. Black history, for too long, has been elided in schools. Black people have been usurped of their stories and value in this space which is so fundamental to the shaping of minds, attitudes, and perceptions.

Yet, even with this common knowledge, the content and culture of schools still favors versions of U.S. and world history that are ethnocentric, Eurocentric, and in need of decolonizing. If historical knowledge is a constructed and contested space, all educators need to own the tension between knowledge and power that is too often underappreciated. History is never neutral. Knowledge is rarely objective. Stories of progress, American exceptionalism, and frameworks that portray this country as a shining city upon a hill continue to bury and marginalize accounts of suffering and persecution, let alone the multiplicity of peoples who have come to inhabit this country.

Teachers can disrupt this type of education. The words a teacher uses and the content they feature all go towards reinforcing or dismantling a status quo in schools and society. The unfortunate reality that school works for some students but often at the expense of others who are deserving of so much more can be addressed in classrooms even as structural changes are taken up by administrators, school boards, and the community.

Black history is American history. They are not separate and cannot be disentangled. One cannot be an entire course of study and the other something relegated to the periphery. Under-told narratives must be elevated and given the attention that is long overdue.

As the world processes yet another video of the untimely death of a Black person in the United States, we are tempted to focus on the history of Black victimization in schools. There is a need to have a reckoning with this history. A brave and honest telling of U.S. history cannot exist if this persecution and oppression is sanitized from classrooms. Enslavement, segregation, lynching, disenfranchisement, criminalization, mass incarceration, and structural racism all need to be introduced in social studies classrooms. But, this is not enough.

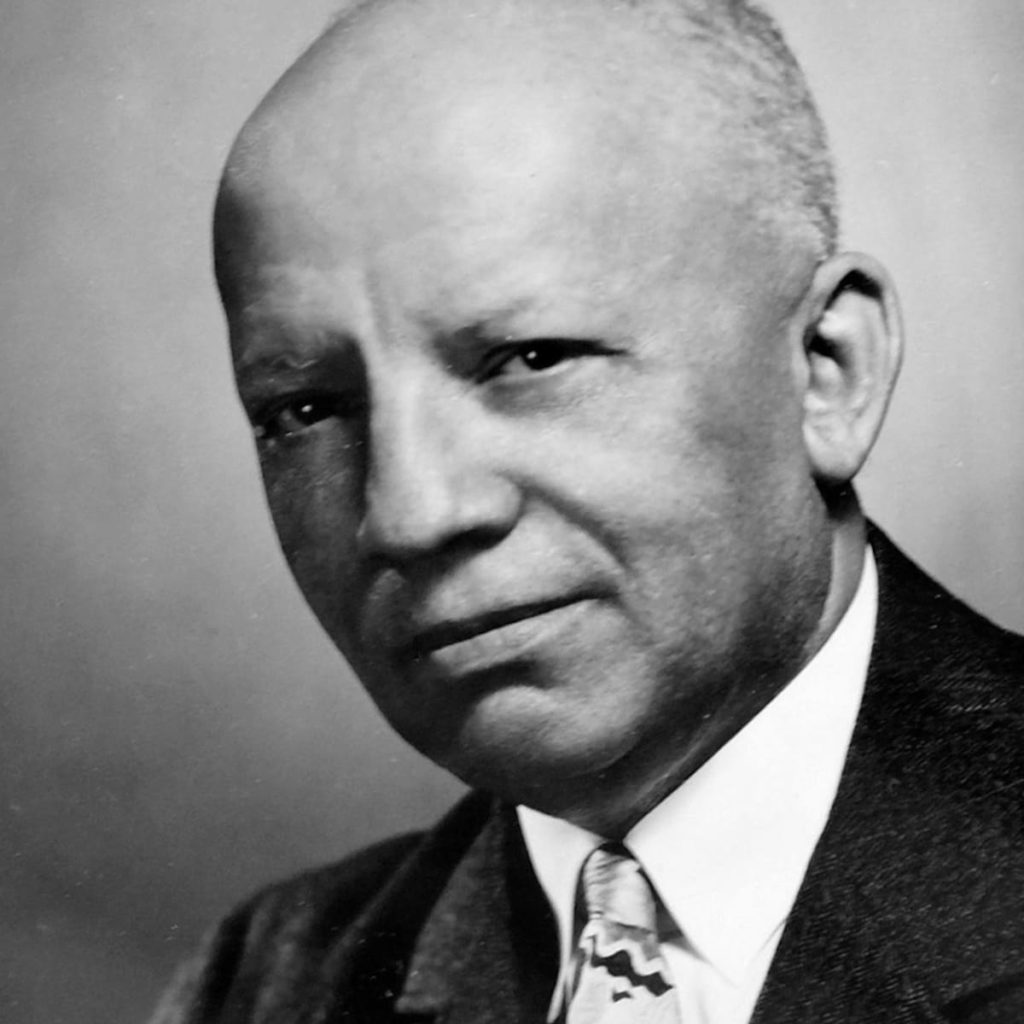

Black history, also known as an inclusive and more fully developed American history, cannot portray Black people only as victims. This would be its own disservice to the members of this community, past and present, and all students who receive this education. Black people have always been and continue to be dynamic and pluralistic, never experiencing a monolithic experience. Even during the long centuries of abuse, agency and voice have remained staples of the community and its experiences. For example, the teaching of lynching is incomplete without introducing the anti-lynching journalism and activism of Ida B. Wells or Mamie Till’s decision to publish the images of her son, Emmett, at his funeral after his lynching. It is incomplete without the haunting beauty of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” or Nina Simone’s “Mississippi, Goddam.” Without knowing about the establishment of the NAACP and the writings of Carter G. Woodson, Black history becomes the story of people acted upon yet who have no ability to act themselves. This is a brief and woefully incomplete list of individuals who embody the political, artistic, and cultural contributions of Black people to the fabric of society in the United States. More is needed. It was needed yesterday. It will be needed tomorrow.

Teaching Black history could never afford to be absent in schools or presented as an incomplete footnote. Educators can work to continually expand its presence in classrooms and at the same time avoid the poles of one-dimensional victimization and glib cultural celebrations.

Black history is complicated, nuanced, and full of sorrow and accomplishment. Students in the United States deserve to see the full range of experiences and humanity found within Black history. Black people deserve to see their meaningful, lasting, and long neglected historical contributions honored.

Credit must be given. Attention is deserved. Social change and justice require dedication and commitment. The problem of ending structural racism and racial injustice will not happen in schools alone but the narratives found in classrooms and the ways Black people are represented within them can go a long way towards building empathy, humanizing the other, and promoting a more compassionate and pluralistic society.

Daniel Osborn, Ed.D. is a program director at Primary Source, an education nonprofit committed to promoting multicultural, global, and culturally relevant approaches to teaching and learning. He is the author of Representing the Middle East and Africa in Social Studies Education: Teacher Discourse and Otherness.