This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

Connection in Native American Organization and Interaction

Connection lies at the center of Native American organization and interaction. Under their cosmogony, we are all connected to the spiritual world, which itself is intertwined with the natural world. Use of the natural world in turn forms the patterns of interaction needed within the village to support its subsistence, and these patterns of behavior within the village carries over into how the group relates to other villages, groups, and tribes. Let’s take a closer look at how all of these levels interact and connect with one another.

The Great Spirit gifts use of the land to Native Americans. From this beginning premise, land is something that cannot be owned, and the rights to use it is conferred on the group, not any individual. Significant landforms—mountains, lakes, swamps—are imbued with spiritual meanings given their connection to the Great Spirit. Tribal ancestors, who protect the tribe and who are buried in the land, additionally strengthen the connection to the land. Sachems, as leaders of the group, are vested with the responsibility of using the land wisely so as not to violate the gift of the Great Spirit, and with the help of the shaman, they worked to ensure the fertility and productivity of the land. Before Europeans took control of the land in the Americas, sachems were empowered to negotiate with other sachems over boundary disputes, but these disputes were not over ownership of the land but rather over usage rights of shared land. When we later turn to examining early contact with European settlers, understanding this relationship between Native Americans and the land will be crucial.

For Native Americans living in eastern North America, the universe was morally neutral, with potentially hostile or potentially friendly spiritual forces all around them. In this cosmology, some of these spiritual forces are human; most of them are other-than-human. Everyone—people, animals, and spirit forces—have to work together. Humans need to bond with one another in families, clans, and villages, and the individuals in them all need to work together and within nature for the greater good of the group. In order to live, animals and plants need to offer themselves voluntarily as food. And powerful forces like the sun or the wind need to be placated to work on everyone’s behalf. To make this entire interconnected system work, the exchange of goods and obligations among all of these entities needed to be reciprocal and carried out with respect, so ceremony was employed to ensure that it did.

People who lived from the Chesapeake, up the eastern coast, over present-day Canada, and back down to the Ohio River (forming a vast inverted U: see the map above) all spoke Algonquian languages (including the Nipmuc). These languages were more loosely connected than the Germanic and Romance language families in Europe, and each language had myriad dialects, because each community was fairly independent from the others. But that does not mean they were disconnected. The great river systems throughout this region enabled trade routes and communication channels that have existed for millennia. Neighboring peoples exchanged food, raw materials, tools, knowledge, and weapons. Long-distance trade tended to involve more exotic materials, such as marine shells and beads to make wampum.

Major disputes between groups were handled with highly structured diplomacy. The Iroquois, neighbors to the Algonquians, employed an elaborate nine-stage diplomatic process when handling major disputes. After initiating a formal invitation to meet, the visitors arrived at the site of the council in a ceremonial procession. Upon arrival, the host offered rest and comfort to the visitors, who are presumed to be tired after having conducted a long journey. The two sides exchanged “Three Bare Words” of condolence in order to clear any grief-inspired rage that could prevent clear communication, and then everyone rested at least one night. The next day, after performing a more extensive Condolence ceremony to cleanse the minds and wipe away any lingering ill feelings, the sides then recounted the history of the two peoples’ relationship with one another, their peaceful interactions, and the manners taught to them by their ancestors. After all of these preliminaries, the work of negotiating the treaty would begin to take place.

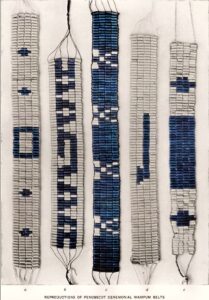

Through the course of the negotiation wampum was exchanged to give the words validity. Wampum was more than a valuable commodity. The carefully woven patterns of beads and shells served as mnemonic devices to help the negotiators remember the messages they were empowered to deliver by the group, and they served as reminders of promises made years before. One’s reputation, in essence, was embodied both in the beads and in their exchange, so when Europeans jokingly tell stories about how the island of Manhattan was “purchased” for a handful of trinkets, more was going on in the exchange, at least in the minds of the Native Americans, than the story normally reveals.

During the negotiations, both sides were required to listen politely to the other side and not respond with anything of substance until the following day. Immediate replies were taken to mean that the speaker did not have the authority to speak on behalf of the group and that the proper wampum had not been prepared. Such exchanges could go on for days if not weeks. Negotiations mainly focused on compensating victims rather than punishing the perpetrator, whereas the reverse is true today. When a final outcome was agreed upon, the conference was concluded with a huge feast and an exchange of material gifts, such as food, cloth, tools, and weapons.

The effect of such elaborate ceremonial negotiations was to lower tensions, hear out everyone’s grievances, and empower the proper people to negotiate an acceptable solution to the problem. The negotiations took place in front of dozens if not hundreds of men, women, and children to give evidence that their representatives had broad political support. The people also served as witnesses to the continuity of these decisions to the past, to the need to remember the covenant that was just created, and to continue to live as good, peaceable neighbors. In other words, connection and harmonious balance were the primary concerns of all involved.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Works Consulted:

* * *

Janet Parnes presents Dolley Madison

On Wednesday, March 29 at 6:30 p.m. in the Galfand Meeting Room at the Westborough Public Library, learn about one of our country’s transformative First Ladies when Janet Parnes presents “Quaker Girl Takes Washington’s Center Stage: The Influence of Dolley Madison.”

In her presentation, Parnes will take on the role of Dolley Madison, who softly stepped outside the social norms of Washington’s high society to establish new standards of decorum, introduce women into the politics of the day, and earn the respect of both military and civilian populations.

This free event is funded by the Westborough Cultural Council, and you can register for it here: https://westborough.assabetinteractive.com/calendar/janet-parnes-presents-dolley-madison/.

* * *

Take a Westborough Architecture Tour (from the Warmth of Your Own Home)

As part of the 300th Anniversary celebration of Westborough in 2017, R. Chris Noonan and Luanne Crosby conducted a series of architecture tours around town and recorded them. With the help of Westborough TV, the two of them have now been working on editing the recordings and the second of these tours is now available online: https://westboroughtv.org/architectural-cultural-walking-tour-series-walk-2-archeology-primer-westboroughs-pre-history/.

This tour centers around Cedar Swamp, which was filmed on a frigid winter day, and explores the pre-history, environmental protection, and importance of the area. The guest speaker on the tour is Michelle (Kamala) Gross, owner of Westborough Yoga and a trained archeologist who worked on this site back in the 80’s.

* * *

Nature Notes

I recently attended the Worcester Art Museum’s annual “Flora in Winter” event where one of the floral displays used pussy willows. Seeing them reminded me how come spring when I was growing up, these twigs carrying hairy buds that felt as soft as cat’s fur always seemed to find their way into our house from the large, thriving bush in the corner of our backyard—one of the few plants we seemed to be able to grow successfully.

Learn more about pussy willows and other early signs of spring in Annie Reid’s Nature Notes for March: https://westboroughlandtrust.org/nn/nnindex?order=month#March.

* * *

New Cabinets, New Look!

The Westborough Center has just added a new row of shelving to its room, which increases storage capacity for our town’s growing collection of historical records and documents.

You can learn more about the collections that are stored in the room by visiting the Westborough Archive catalog: https://catalog.westborougharchive.org/. If you spot anything that you would like to see in person, ask me or another librarian to pull it out for you. We are always happy to do so.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.