This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

First Contact and Population

When discussing Native American history, both before and soon after European arrival in North America, we need to note an irony: in order to piece together the history of Native Americans before European contact, we need to rely on European sources after contact.

Native Americans did not have written language, and consequently they did not have recorded history in the way that Europeans did. Instead, their histories were handed down orally, and as such they were intertwined in their mythologies and belief systems—much like early Greek history was at one point handed down orally: think The Iliad and The Odyssey and their mix of history and mythology. By the way, Homer’s two epics about the historical Trojan War (which took place in the 13th century B.C.) were captured in print in the 8th century B.C., right around the time that the Greeks (re)invented their writing system. Eventually, the Greeks also invented history as we conceive of it today, with Herodotus being considered the first historian, followed soon after by Thucydides. This Western concept of history requires written language, so that we can describe and record events, reflect on and attempt to verify them, and construct a narrative of those events that itself is constantly open to reevaluation and revision.

With the absence of a written language, our knowledge of early Native American history, then, is essentially dependent on two major sources. One is archaeology—a practice of ascertaining how people lived during times of prehistory that was invented much later in time in the eighteenth century. The second source is documents about Native American life that were written around the time of contact that were created by Europeans and written for European consumption back home. Naturally, these early records and descriptions of Native American life have a heavy European bias, and so we need to “read between the lines” of these early accounts to try to arrive at a better and more truthful understanding of Native Americans both before and around this time of early contact.

Some of these early works include accounts by French Jesuit missionaries, records of negotiations between Native and European imperial governments in Albany, and documents relating to the praying towns in Massachusetts first led by John Eliot. Historian Daniel K. Richter contends, “Read carefully, each [of these bodies of records] in its very different way reveals Indian people trying to adapt traditional ideals of human relationships based on reciprocity and mutual respect to a situation in which Europeans were becoming a dominant force in eastern North America.” The implication here is that we need to be just as, if not more, attentive to the Native American perspective when reading these documents if we are to ascertain properly their motives and positions when interacting with Europeans.

* * *

I hope that you have found my explorations of Native American life before European contact over the last several months to be as compelling as I have found them to be. But now we are to the point in my investigation where things become really interesting, because we get to see what happened when two entirely different cultures, European and Native American, came into contact and how their differences informed their relations with one another.

When Columbus landed in what is now the Bahamas in 1492, or when Vikings established a small colony in Newfoundland in 1021—pick whichever narrative you prefer—and first encountered the Indigenous people living there, the meeting marked the full circling of the globe by human beings. This odyssey first started in Africa 60,000 years ago when human beings fanned upward and out of Africa, encountered Neanderthals, who had separated from our common human lineages 500,000 years ago, and then moved east across Asia and west across Europe until each genetically identical strand finally met up in eastern North America. Talk about an epic journey!

We will never know exact statistics, but the population of the area of North America east of the Mississippi at the time of Columbus’s arrival may have been more than 2 million Native people. These numbers soon shrank rapidly due to the diseases that European explorers and settlers brought with them and to which Native Americans had no immunity. As for the number of Europeans, by as late as 1700 their total population only amounted to around 250,000, and they were mainly confined to the coasts along the Atlantic seaboard. By 1750, however, a decisive shift had taken place, where European populations and their enslaved African workforce exploded to 1.25 million people while the Native population shrank to 250,000. By the time of the American Revolution—more than 280 years after Columbus’s landing—the number of European and African Americans finally brought the population of this eastern part of the continent back to where it was before at 2 million.

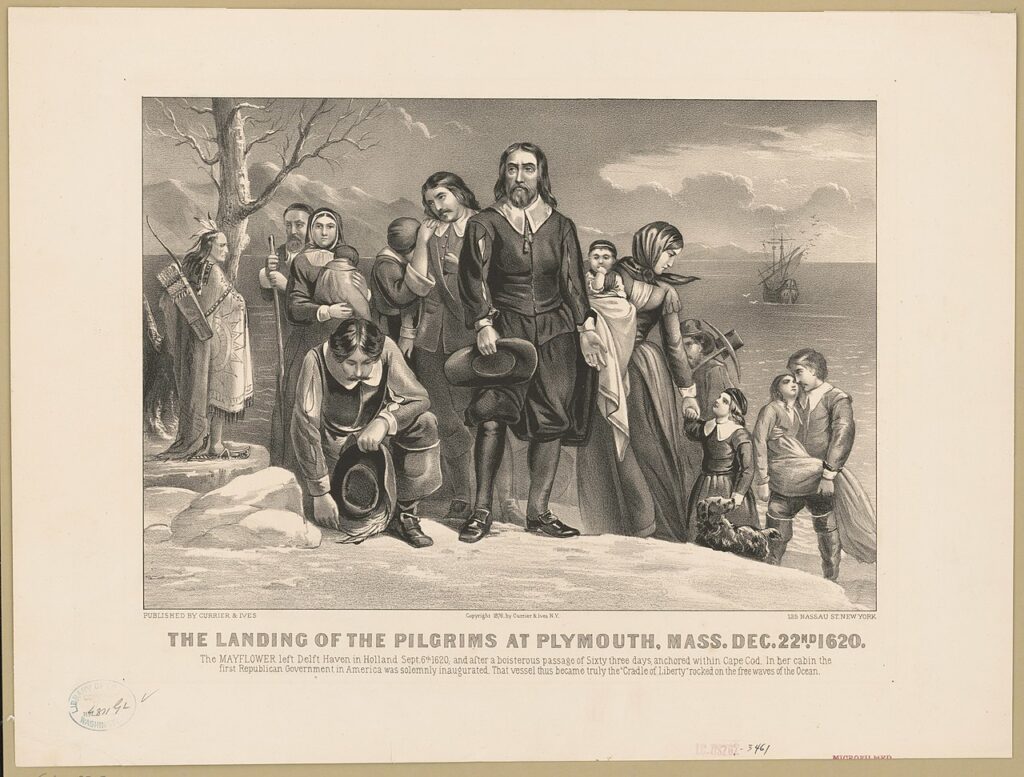

In 1600, just before the Pilgrims’ arrival, the total Indian population of New England was between 70,000 and 100,000. But when the Mayflower landed in Plymouth in 1620, a recent outbreak of disease had killed nearly ninety percent of the Wampanoags who were living there. The tired and hungry colonists were overjoyed to discover a vacant Native village and interpreted the cleared land as a reward for their biblical exodus. While exploring the village, they discovered, and promptly took, a deposit of corn that the Wampanoags had hidden away for themselves. For Native Americans who lived in southern New England, grain made up one-half to two-thirds of their diet, and it could be stored during the winter months so as to stave off starvation and be used in the spring as seed. In taking this stash of corn, then, the Pilgrim’s first decisive—and foretelling—action upon landing in North America was an act of theft.

When Europeans first entered North America, there was no part of the continent that was not inhabited and ruled by a sovereign Indian regime. The notion of “unsettled wilderness” that was ripe for the taking was a convenient myth first created by the Pilgrims. This myth helped them justify to themselves the taking of the Native American village and its land and ever since has informed the view of many historians interested in justifying European expansion on the North American continent. More recent historical evidence, however, does not support this notion of free and uninhabited open space.

If disease had not ravaged the Wampanoags before the arrival of the Mayflower, the Pilgrims’ landing would certainly have played out a lot differently. Next month, we are going to take a closer look at how the spread of disease among Native Americans impacted other elements of first contact between the Indigenous and European peoples.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Works Consulted:

* * *

New Native American Resource

To accompany my Westborough History Connections series, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough,” I have created a new bibliography: Native American Resources in the Westborough Public Library.

This bibliography lists primary and secondary sources relating to Native American history in both Westborough and New England, so if you are interested in learning more about the issues and ideas that I have been exploring in my series, this list of resources is a great place to start.

* * *

A Major Parkman Publishing Announcement

I am just about to finish reading Culture: The Story of Us, From Cave Art to K-Pop by Martin Puchner. In his book, Puchner argues that culture by definition is created through sharing and incorporating information both from the past and from other cultures that are not our own. While making this argument, he describes the many ways that knowledge is passed down to future generations and influences other cultures—from monuments, to oral story-telling practices, to writing on papyrus, to libraries and archives, etc. But he also shows how precarious all of these information transmission systems really are and how easily systems that we often take for granted can easily disappear. Central to this transmission of information is the humanities, which is the prime driver of knowledge and human civilization.

To this end, the Westborough Public Library is an important transmitter of knowledge and information, not only to our community but to the world. One of the library’s initiatives that I have written extensively about is the Ebenezer Parkman Project (EPP), which makes available both the works of Rev. Ebenezer Parkman, Westborough’s first minister, and related Westborough town records. Taken together, these documents provide the fullest picture of colonial life in a rural, New England community that is available anywhere. Now, the Colonial Society of Massachusetts (CSM) will be formerly publishing much of the EPP material on their website. My co-directors of the EPP—Prof. Ross W. Beales and Dr. James F. Cooper—and I have already started working with the CSM on converting and organizing this content for publication.

The importance of the Parkman and Westborough records will become even more apparent once they are published on the CSM website (we do not have a set publication date yet). But it is possible that the content of this project would never have made the light of day had it not been for the Westborough Public Library. Prof. Beales, whose scholarship forms the content of the project, recently admitted to me that if our other co-director and I had “not envisioned the EPP, most of what I’ve been doing would have ended up in a digital graveyard.” The Westborough Public Library provided Prof. Beales with the means to make his extensive scholarship on Parkman and Westborough available; otherwise, it would have sat on his computer and, at some point, probably disappeared. Now, with its publication through the CSM, this monumental project will find a long-lasting home where scholars and anyone else will freely be able to access and read it.

* * *

A New COVID History Podcast

Mary Botticelli Christensen has been tirelessly collecting stories from Westborough residents about their experiences during the Coronavirus Pandemic. Now, in conjunction with Westborough TV, she has gathered them all together into an engaging podcast series called, When the Pandemic Came to Town: How a Small New England Town Survived with Resilience and Kindness. You can learn more about this project and access links to listen to the podcast on Amazon, Spotify, or Apple platforms by visiting this Westborough TV page: https://westboroughtv.org/when-the-pandemic-came-to-town/. (BTW, I make an appearance in the first episode, if you are interested.)

* * *

April Nature Notes

A section of my vegetable garden has been giving me disappointing results in recent years, probably due to insufficient sun, so I’m toying with the idea of turning this bed into a local plant and wildflower garden. Perfect timing, then, to read Annie Reid’s latest Nature Notes essay on whitlow grass and the first wildflowers of spring!

And you can read more of her essays about the natural goings-on on in Westborough during April here: https://westboroughlandtrust.org/nn/nnindex?order=month#April.

* * *

Protecting Open Space in Westborough

Speaking of Westborough nature, next month’s Westborough Historical Society program will celebrate a quarter-century of preserving open space and creating trails by the Westborough Community Land Trust on Monday, May 8, at 7:00 on Zoom. WCLT leaders will describe the history of the organization and all that it has accomplished over these years.

This program is FREE, and you can register for it through this link: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZErcumoqjIvHNQu1LnSSWnAJXIzA2im_3ID.

* * *

Travel Back in Time . . . By Unplugging

Even those of us who lived before the era of cell phones and computer screens have a hard time remembering what it was like to live without them. Now, for one week, you can return to those times (or, if you are younger than I am, get a feel for what life was like back then) by participating in Westborough Connects’ “Westborough Unplugs: Screen-Free Week” from April 30 to May 6.

To help us unplug for one week, Westborough Connects has a host of fun, computer-free, programs lined up to help get us through this admittedly difficult challenge, including a community bike ride, a “Book & Seek” here at the library, an exploration of Nourse farm, and a nature walk hosted by the Westborough Community Land Turst. Click here to find a complete list of events with links to more information, as well as details about their “Spring into Wellness” program on May 7.

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.