New documentary, “If You Cross This Boundary, We All Die,” is the latest example of their work

Years ago, teachers would roll a bulky box television strapped to a metal frame into the classroom, throw a tape in the VCR, dim the lights and begin playing a history documentary that was as old and outdated as the asbestos covering the school’s pipes.

By the end of the film, half the class would be asleep and the other half that did not nod off were doodling in their notebooks.

That was then, and this is now.

In recent years, educators like Self-Evident Education have been on the cutting edge of how students absorb history, especially when it comes to the history of race in the United States.

By using interactive multimedia documentary films that spark in-depth discussions on a given subject matter, Self-Evident Education multimedia has the ability to build immersive worlds for students to enter, through which they can understand the past.

According to Self-Evident Education, “many teachers want to engage with the important histories and legacies of systemic racism, but they don’t have the experience or resources to know how to do it honestly and rigorously, and so they avoid it, which continues to perpetuate a lack of deep understanding of our past.”

Michael Lawrence-Riddell, an award-winning public school educator, conceived this platform in response to the urgent need for our society to honestly and rigorously engage in work to understand the histories and legacies of race and institutional racism.

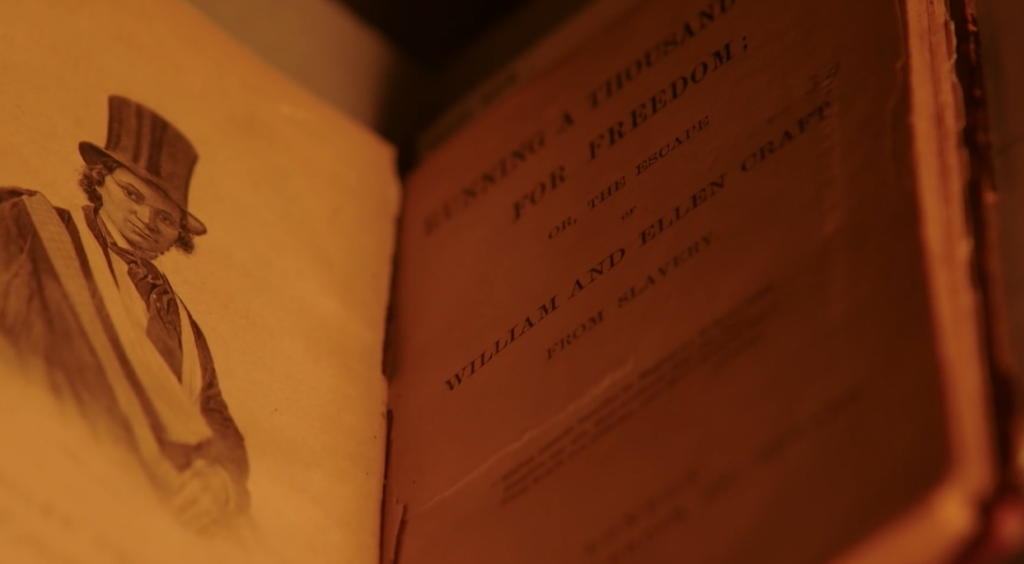

Their latest documentary, “If You Cross This Boundary, We All Die,” an original film funded in part by a Mass Humanities Expand Massachusetts Stories grant, tells the story of famed abolitionists Ellen and William Craft, who escaped enslavement through Ellen’s passing as the white male owner of William.

Mass Humanities recently sat down with Lawrence-Riddell to talk about Self-Evident Education’s learning model, the recent documentary, and the tools they are providing to reshape education in the Commonwealth.

Mass Humanities: Can you describe Self-Evident Education’s learning model?

Michael Lawrence-Riddell: The model begins with a short documentary film like “If You Cross This Boundary, We All Die.” Then underneath the film, you have all these follow-up resources that educators, students and community organizations can use to dig deeper into the topics that are covered in the film. The films themselves are multimedia and the reason we refer to them as such is because we’re really intentional about having storytelling that is different than traditional documentary films.

MH: What sets these documentary films apart from others?

MLR: We’re really intentional about using a mixture of primary source documents, original footage and animated or illustrated content, along with music and editorial choices that really fit in with the ways young people are used to consuming media these days. We’ve really made some intentional aesthetic choices that I think differentiate our documentary films from anything else that’s out there.

MH: What led you to settle on this model?

MLR: At the very beginning of the project, when it was still just an idea in my mind, one of the first people I sat down with was a colleague of mine, Dr. Eric Soto-Shed. He’s a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. We knew we wanted documentary films to be the center point, so Eric and I sat down and thought, ‘Okay, so each time we tell a story, what are the essential ideas? What are the big ideas that we want all of our stories to interact with? What are the questions we want people to be asking after they see our material?

Those were sort of the linchpins. Those are the parts of the matrix that we use when we decide which stories we think are the right ones to tell and how we want to tell them.

The next thing we did was think about the skills that we want students of history to practice and be able to do and how we can create an architecture of activities that will elicit those kinds of skills from the students who use the materials. Every lesson has a film and then there’s a common set of activities that look at the same kinds of skills, but the content depends on the film.

MH: It seems like a fascinating model for educators and different from those old documentaries we were forced to watch as students years ago.

MLR: After Eric and I thought about the architecture of the curriculum, one of the next steps was talking with my colleague, Bayeté Ross-Smith, about the idea. Each time we talked, he understood more and more about what I was envisioning.

His suggestion was to slow down, follow the course of American history, and rewind to before the American colonies. We started looking at a timeline from 1400 to the present and he wanted me to break that history into 10 separate eras. Then he wanted me to think about three to five stories in each one of those eras. If we put these eras together as a whole, it helps us have a clearer picture of American history and the ways in which race has been created, codified and weaponized throughout that history.

MH: How did you decide to tell the story of William and Ellen Craft?

MLR: The story of William and Ellen Craft has always fascinated me. When I was teaching middle school English, I actually started writing a young adult novelized version of the story because there’s so much in it that I think is so gripping. I think it allows us to interrogate some of these systems of identity throughout American history.

This is a woman who is enslaved and legally classified as a black female, but she looks like a white woman. So she disguises herself as a rich, disabled white man. Just think about all of those masks and identities that she’s putting on in order to gain her freedom. The other set of ideas that it allows us to explore around the history of race in America are our infinite rights. They decided to self-emancipate because they wanted children, and they didn’t want those children to be born into slavery.

The film allows us to investigate the story of William and Ellen Craft and the ways in which abolitionists unite and use violence as a political tool to resist the Fugitive Slave Act. The story also helps us explore and poke holes in the fragility of some of these social concepts. The concept and construct of whiteness are sort of fragile, and William and Ellen Craft are able to exploit that concept to liberate themselves.

MH: Others, like Mary Milburn and Maria Weems, used the same sort of tactic to gain their freedom. How do you connect those stories to the story of William and Ellen Craft?

MLR: One of the follow-up activities that we have in every lesson is called ‘echoes, connections, and projections.’

This asks students or educators engaging with the film to look for stories that we have told that feel sort of like an echo to give it context.

Then the connections are the other things that happen after this moment in history that are connected to it, why this moment feels like a precursor to other things, and how we can examine the ways in which these stories connect.

Echoes can actually give projections, and we ask students to look at how this story influences other moments in history that happened after.

To me, the projection aspect is really the most exciting piece of what educators and communities can do with our content. How do we use that understanding of our past to analyze our present and then project ourselves into a better future? How do we use this history to understand our present so that we can better envision and build a just tomorrow?

I think all of our curriculum, all of our films and all of the follow-up questions that we are asking teachers and students to engage with are sort of undergirded by that general philosophy. The past begets the present and the present creates the future. We’ve got to understand our past and we can understand our present so we can build a better future.