This essay is part of a new Westborough History Connections series called, “A Meeting of Two Cultures: Native Americans and Early European Settlers in Westborough.” Click here to start at the beginning of the series.

Land and Disease

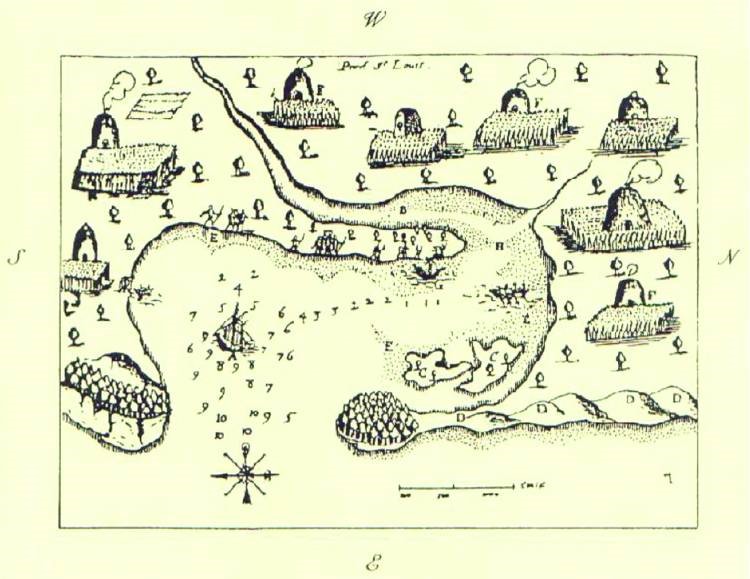

When the Pilgrims landed in North America in 1620, Native Americans and Europeans had already been in contact with one another for over a century, so by the time the English started moving from sporadic coastal areas into the interior of New England, Indigenous cultures had already been disrupted by European contact, most notably, by infectious diseases for which they had no biological immunity.

I began my last newsletter pointing out how much we have to rely on European accounts when trying to piece together the history of Native Americans before European arrival. But extrapolating this history is even more complicated. The impact of disease on Indigenous life and culture was so fast and so profound that even if early European accounts of their encounters with Native Americans were entirely accurate, the life they would be describing would already have been distorted from what it was truly like before Columbus’s arrival.

When the English and the French first began landing on the coasts of eastern Canada, Maine, and nearby islands in the sixteenth century, their encounters with Native populations soon resulted in deadly epidemics that had a possible overall mortality rate as high as 80 percent. The period after 1600 was particularly fatal, when European families with children, who were more likely to carry “childhood” diseases, began settling in eastern North America. Between 1616 and 1618, an epidemic or series of epidemics along the southern New England coast killed perhaps 75 percent of the coastal Algonquin population.

No doubt, this rapid decline in the Indigenous population when combined with the increasing influx of European settlers together made navigating these new circumstances by Native Americans even more challenging—and frightful. Demographic collapse upended social status systems within villages and between tribes. It shattered families, who were then forced to recombine and reinvent themselves in order to survive. It forced Native Americans to abandon old means of feeding and supporting themselves and adopt new economic practices, such as participation in the fur trade. New alliances, and new antagonisms, were created among Indigenous people as a result of this depopulation, which made it difficult to create a united front when facing their new neighbors from overseas. The scarcest resource for Native Americans, in other words, had become their own people. These circumstances were all at play in the abduction of the Rice Boys here in Westborough, which we will look at in more detail later on in this series. Nonetheless, Native Americans continually demonstrated endurance and perseverance in their attempts to preserve their spirit and build back what they used to have in the midst of these unprecedented conditions.

By 1670, New England colonists numbered over 50,000 and outnumbered the local Indigenous population three to one. As we have already noted in the previous newsletter, this depopulation made it easier for Europeans to justify taking Indian lands by interpreting the abandoned villages and fields as a sign from God that they were destined to take over and (re)populate the land. Even more, New England towns repeatedly sprung up on the very sites of these empty villages, as Europeans took advantage of land that Native Americans had already prepped to accommodate housing. The land itself even began to change as a result of Indian depopulation. Native Americans regularly conducted annual burnings to clear land so that they could continue to plant their crops. But with these burnings no longer taking place, the grass that stood in these open fields when the Pilgrims arrived in 1620 was already taken over by forest by the time the Puritans arrived to found the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630.

In and around Westborough, the Nipmucs also experienced plague in 1633, but it would be another twenty years before Europeans began to encroach on their land, since land grants and settlements did not start in east central Worcester County until 1654. Through this time, Nipmuc leaders seemed to have charted a middle course in dealing with the English that delayed either accepting English presence or driving them out. This more peaceful approach, though, may have sealed their fate. In the 1640s, if the Nipmucs had united with other tribes, they together probably would have had enough numbers to overwhelm the English and drive them out of the nascent colony. And despite their plagues, the Nipmucs still had the numbers to contribute more warriors than any other local tribe to King Philip’s forces during the war that was named after him. But their peaceful delay meant that by the time King Philip’s War started in 1675, the Massachusetts Bay Colony had grown so big in size and sophistication, and was able to play the various tribes off one another, that the Europeans were able to secure a permanent advantage.

The struggle over control of the land, which ultimately led to the creation of the United States, rightfully receives the bulk of our attention when looking at the history of European settlement in the Americas. The basic framework of this history also conveniently makes for gripping Western movies, if the popularity of this genre starting in the 1950’s is any indication. But when we flatten the Native-colonist narrative into a simple one of “Cowboys and Indians” with a constant fight for territory and control of the land, we lose sight that at least here in New England, Native Americans and European settlers lived together for hundreds of years—and still do to this day. How these two groups lived side-by-side will now be the focus of the rest of this series.

—Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Works Consulted:

* * *

A New Major Resource for Westborough Historians and Genealogists

A new resource for Westborough historians and genealogists has just been made available by Prof. Ross W. Beales, Jr. on the Westborough library’s Ebenezer Parkman Project website. “Reconstitution Data for Westborough Families” now appears on the Westborough and Its People during Parkman’s Time web page, which already offers a bevy of historical information about early Westborough residents.

In this new resource, Beales has gathered together information about people who lived in Westborough in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries from a variety of sources: published vital records of Westborough and other towns; Ebenezer Parkman’s and Breck Parkman’s diaries; the Westborough church records; genealogies; town histories; probate records; newspapers; and data from the websites of AmericanAncestors.org and Ancestry.com. The document itself is still in process, and Beales warns that there are elements in it that may need correction. Even so, it presents a fascinating picture of Westborough society during this early time in our town’s history.

* * *

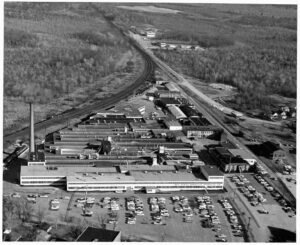

New Mini-Exhibit: The Bay State Abrasive Company

Check out the new exhibit in the display case outside of the Westborough Center on the history of the Bay State Abrasive Product Company, which used to be located where the Bay State Commons is today. The company made grinding wheels and other abrasives for the automotive, steel, aerospace, and metalworking industries and for decades served as the largest employer in town, at one point employing over 1,100 people.

The display features newsletters and pictures of the factory and its employees that show how important this business was to the life of our town.

* * *

May Nature Notes

My dog Sadie loves to run after her toy opossum after my wife throws it for her, but rather than retrieve it, she will prance around and taunt Martha with her prize in an attempt to get her to chase her and take it back. I’m just glad it isn’t a real opossum!—although it sure does look like the one in the picture that Garry Kessler took for one of Annie Reid’s Nature Notes for the month of May, where you can read all about real opossums and other natural phenomena that appear during this lovely month!

* * *

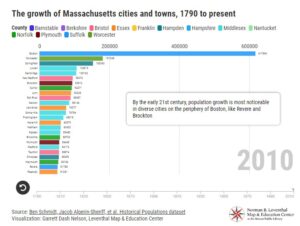

Learn About Population Growth Over Time in New England’s Cities

What can a visualization of population growth tell us about different moments in New England’s economic geography? Watch a dynamic chart that shows how the populations of the largest cities and towns in Massachusetts and their ranking orders have changed over time, and then read about what it all means in the Boston Public Library’s Leventhal Map and Education Center’s web article, “Growing New England’s Cities.”

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Center Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox.

You can also read the current and past issues on the Web by clicking here.