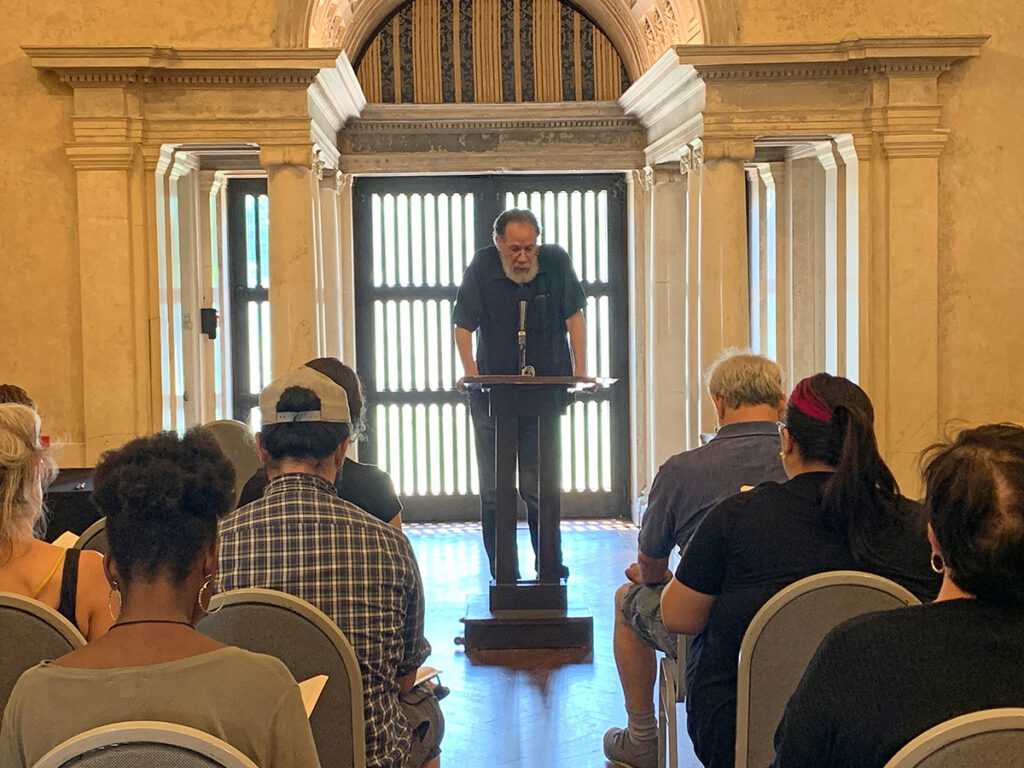

Martín Espada is an acclaimed poet, editor, essayist, and translator. He is also one of four individuals being honored this year with the Governor’s Award in the Humanities. Espada’s 2021 book of poetry, Floaters, won the National Book Award for Poetry. We recently sat down with Espada at his home in Shelburne Falls to ask him about his craft, how the humanities intersect with his work, and how our present moment calls for “poems of love.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Martín, thank you for sitting down with us. Why don’t we start at the beginning. When did you first hear about the work that Mass Humanities was doing in Massachusetts?

I remember Mass Humanities from the eighties. I attended Northeastern University Law School in Boston and graduated from there in 1985. I went to work for an organization called META, Multicultural Education Training and Advocacy, a nonprofit, public interest law firm specializing in the rights of linguistic and cultural minorities. Camilo Pérez-Bustillo was my fellow attorney and close friend at META.

We decided to stage several poetry conferences and festivals geared towards a community nobody was serving—the Latino community. Camilo discovered the existence of David Tebaldi at Mass Humanities. And David Tebaldi came through big time.

For the first time, we had a budget. David Tebaldi was the first person with any state agency who recognized what we were trying to do. And we did it. Then we went back to the well for more money. We began our “cultural advocacy” with a focus on Puerto Rican literature and political struggle, then expanded to the Latino community and communities of color in Greater Boston.

When I saw that this award came from Mass Humanities, what clicked was the memory of David Tebaldi and those grants he gave us to do our work in the eighties.

And you were writing during this time as well.

My life as a poet and my life as a lawyer weaved in and out. I wrote my first poem when I was fifteen, stopped writing, picked it up again, went to college and had the canon aimed at me. That was the end of my literary education.

The wise old men in my life, such as my father, Frank Espada, a community organizer and documentary photographer, and my professor Herbert Hill at the University of Wisconsin, where I got my undergraduate degree in history, said, “You’ve got to go to law school. You’ve got to be a lawyer. Poetry is nice, but what are you going to do with it?”

I was the first one in my family to go to college. We didn’t know there were alternatives. My mother once pulled me aside and asked, “What’s a graduate student? I thought once you graduate, you’re not a student anymore.” We had never heard of an MFA. Therefore, I went to law school. I made the social and political commitment I wanted to make to my community by being a lawyer.

I never gave up on the poetry. I published my first book right before I went to law school and my second book right after I got out of law school, because you do nothing when you’re in law school but law school.

I came to lead a double life. Eventually, the Boston media picked up on it: first The Tab, then The Globe. People were astonished that a poet-lawyer could possibly exist: My god! A poet-lawyer! It’s like a creature out of Greek mythology, with the body of a lawyer and the head of a poet. One of those identities would have to absorb the other one.

From META I moved to Su Cliníca Legal, a legal services program for low-income, Spanish speaking tenants in Chelsea, across the Tobin Bridge from Boston: eviction defense, no-heat cases, rats and roaches, crazy landlords.

Legal services money is soft money, like any other social services, subject to cutbacks. The Reagan administration despised the federal Legal Services Corporation, where we got much of our funding, so there was a constant battle in Congress. We found other sources, but eventually our budget was slashed. My position was consolidated with another lawyer’s position.

I could have bumped him because I had seniority, but Nelson Azócar was a friend of mine who’d come to this country from Chile after he talked his way out of being shot by a firing squad. That’s the gift of gab. Anybody who can do that should be a lawyer. I started looking. I wanted the life of a poet, whatever that meant. I ended up teaching at UMass Amherst in fall 1993.

UMass was looking for somebody who had one book. I had four. I made the transition into teaching there in 1993.

How do you see the public humanities intersecting with your work, both as an educator and poet?

Let’s take a shining example: the Clemente Course in the Humanities. I knew the guy who started it in 1995: the writer Earl Shorris. He was writing about my work in The New York Times Book Review back in the eighties. I wrote him a thank you note. That’s how we met.

I remember when he came up with the idea. And strangely enough, it eventually circled all the way back to me. I read my poems for the Clemente Course in Worcester through James Cocola and the Clemente Course in Brockton through Corey Dolgon. Corey and I tried to make it happen in person, but we ended up doing it on Zoom twice during the COVID era. This was more than a matter of serving the Brockton community—this was a matter of serving that community during the pandemic.

I’m still impressed with the vision of the Clemente Course, still impressed with the students. I’m deeply gratified when I’m able to connect in that way. Poetry should go where it’s least expected. Poetry should go where it allegedly does not belong. Poetry should go to a so-called “non-traditional” audience which is, in fact, the most traditional audience of all. Over and over, I’ve seen it work. The Clemente Course is an excellent example, but you need a big soul like Corey Dolgon to build that bridge between people.

On your website, the description for your book Floaters suggests “Espada knows that times of hate call for poems of love.” Can you speak a little more about this notion?

When I say “times of hate call for poems of love,” I’m thinking of “Floaters,” the title poem of my last book, about two Salvadoran migrants who came to be known simply as “Óscar and Valeria,” father and daughter, who drowned crossing the Río Grande. A photograph of their bodies went viral, sparking outrage, sparking grief and also sparking “trutherism.” A post in the “I’m 10-15” Border Patrol Facebook group charged that the photograph was faked. Between the photograph and this Facebook page expressing the racist bile of certain members of the Border Patrol, I had to respond. That’s how the poem came about.

“Floaters,” by the way, is a term used by certain members of the Border Patrol to describe those who drown crossing over. The hate is apparent.

When I say “times of hate,” it should be obvious we’re surrounded by hate. What do I mean, then, that you respond with poems of love? The first part is to perceive a poem like “Floaters” as a love poem that is motivated by a sense of compassion and a sense of connection that we associate with love, not romantic love, but the love we may share for our fellow human beings.

I also mean it on a more literal level, too. Times like this call for love in any iteration. There are also love poems in that book.

What is the role of that process of finding love or connection in this landscape?

I believe that poetry humanizes, that poetry can provide the kind of intimate human details so often missing when we talk about political or social issues. No matter where we are on the spectrum politically, it’s often reduced to abstraction, reduced to statistics, reduced to categories. Poetry, instead, insists upon the image, all five senses on paper. We’re insisting on giving history eyes, ears, nose, mouth, voice, insisting on looking into the hands and saying, “this, too, is human.” And telling the stories.

I am a narrative poet. This is my vehicle, my mechanism for telling stories. But I tell certain kinds of stories. That’s my effort to humanize the dehumanized. Recognizing that, I’m realistic. I’m up against this tremendous machine of dehumanization that works tirelessly into the night.

Why narrative poetry?

I work from an aesthetic of clarity. I intend to communicate. It may not look like some of the poetry you’ve seen before, poetry you gave up on. Believe me, I gave up on the same poetry. That’s one of the reasons I landed in law school. But I intend to communicate. There are enough barriers that I need to leap, whether they are cultural, linguistic, political, social, historical. I don’t need to be coy about it, or “too clever by half,” as the saying goes. I want to speak in such a way that I’m understood.

Martín, thank you for your time, and congratulations on receiving the Governor’s Award in the Humanities this year.