By Andrea Jones, Director, History Leadership Institute

With Nicole Martinez LeGrand, Multicultural Collections Curator, Indiana Historical Society

Does our daily grind stand in the way of creating necessary change in the field of public history? With the constant Zoom meetings, the project deadlines, and

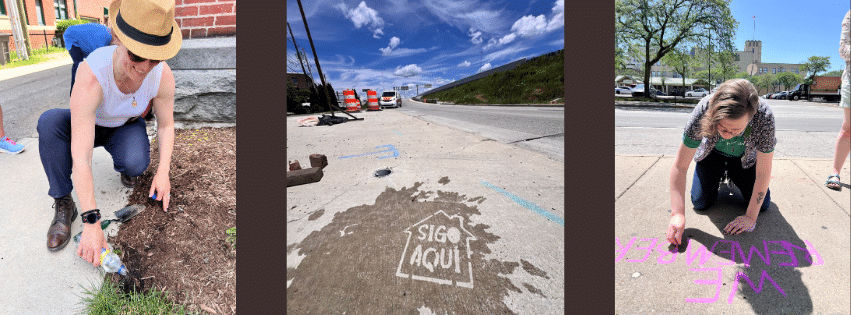

Indianapolis-based historian, Nicole Martinez, poses with the History Leadership cohort (2024) in a formerly Latino neighborhood now buried beneath Interstate 65.

Pictured from left to right behind Nicole: Leslie Pielack, Sam Black, Kelsey Mullen, Erik Mason, Ghazala Salam, Rebecca Peterson, Melissa de Bie, Anne Miller, Helen Turner, Ann Bennett, Julie Wroblewski, Elizabeth Reighn, Vinnie Barraza, Janna Bennett, Aja Bain, Maria Quintero, Tony Pankuch, Kara Knight, and Araceli Hernandez.

the onslaught of emails, the pace of our work can leave us with too little energy to question the status quo or to reflect on whether we are doing the right kind of work. That’s why participating in AASLH’s History Leadership Institute – a program that gives space for experimentation, new ideas, and reflection, can be so powerful.

Using Guerilla Public History to Reclaim Lost History

This need to transcend “business as usual” is the reason I invited this year’s History Leadership Institute cohort to leave their desks for one day – to do some guerilla-style public history while coming face-to-face with their comfort zones and their values. With the guidance of trail-blazing curator Nicole Martinez LeGrand (Indiana Historical Society), we hit the streets to activate a formerly Latino neighborhood in Indianapolis whose history had been excluded from mainstream narratives.

Using creative and temporary tools, we collectively marked, commemorated, and celebrated four locations where a Latino community once thrived in the 1930s – 1960s. With sidewalk chalk, we marked the names of former neighbors and the places they lived, loved, and worshipped as a community.

Members of HLI’s 2024 cohort, Ann Bennett (left) and Tony Pankuch (right) commemorate the existence of an unmarked Latino-American community that was displaced due to the construction of Interstate 65 in Indianapolis in the 1960s. (Photos courtesy Andrea Jones)

I loved the way these stenciled messages helped drive home the point that invisible stories are everywhere – even when the physical structures don’t survive. Nicole, a historian of Mexican descent, explained that the slogan she chose – “Sigo Aquí” or “I’m still here” reflects the practice of commemoration of memory in connection to Mexican culture and of the understanding of death within the context of Dia de los Muertos. While the living celebrate the memory of their deceased loved ones, there are three levels of deaths; when the body stops functioning, when the body is returned to the earth, and when no one is left to remember and commemorate them. So by marking these stories, we were chosing to keep the memory of the neighborhood in the present.

We punctuated the markings by planting a few rogue marigolds (cempasuchil) – a flower associated with memory and Day of the Dead celebrations – within the newly laid sod and sidewalks cracks in the neighborhood. We felt the presence of the old Latino neighbors as we made art and blasted Latino music. Our guerilla-style activation was an act of remembering this neighborhood in a way that held meaning to all the participants – even if our actions were only temporary.

HLI 2024 participants in the activation said:

I found Nicole’s work to be deeply inspiring, and the activity of going out into the streets to “activate” various locations helped to challenge my own perceptions of what public history is, why it happens, and who can do it.

This was a session about collective adventure and joy.

Nicole was able to bring to life the forgotten Barrio, and I was so excited to hit the streets and do some temporary graffiti in honor of the forgotten neighborhood. As a descendant of Mexico, this hit really close to home for me and I was overwhelmed by her leadership. .

Invisible Histories Are Everywhere

Historian, Nicole Martinez-LeGrand stands near an onramp for I-65 in Indianapolis – the former location of a Latino neighborhood (Photo courtesy Andrea Jones)

How many historic places have mainstream historic preservationists overlooked because they were not deemed important at the time – due to racism, historians’ biases, or just simply lack of local knowledge?

These now “invisible” spaces are everywhere. Stories reside beneath our strip malls, between our shiny new condos – and in the case of Indy’s “Lost Barrio” – beneath our interstates. The constitutional right that governments use to seize property for “public use” has long been applied unequally across neighborhoods where marginalized communities live. And often, there is little physical evidence to remind us of those histories.

Participating in a public history activation is extremely powerful for emerging leaders. Not only are they getting the chance to set the record straight, but they are doing it with joy and purpose. They are building the muscle memory for creating real change towards a more inclusive field.

The Importance of Latino Representation in Public History and in HLI

Nicole’s awareness of El Barrio in Indianapolis came through a series of clues that became clear to her only because of her own background as a Latino resident of Indiana with a long family history in the state.

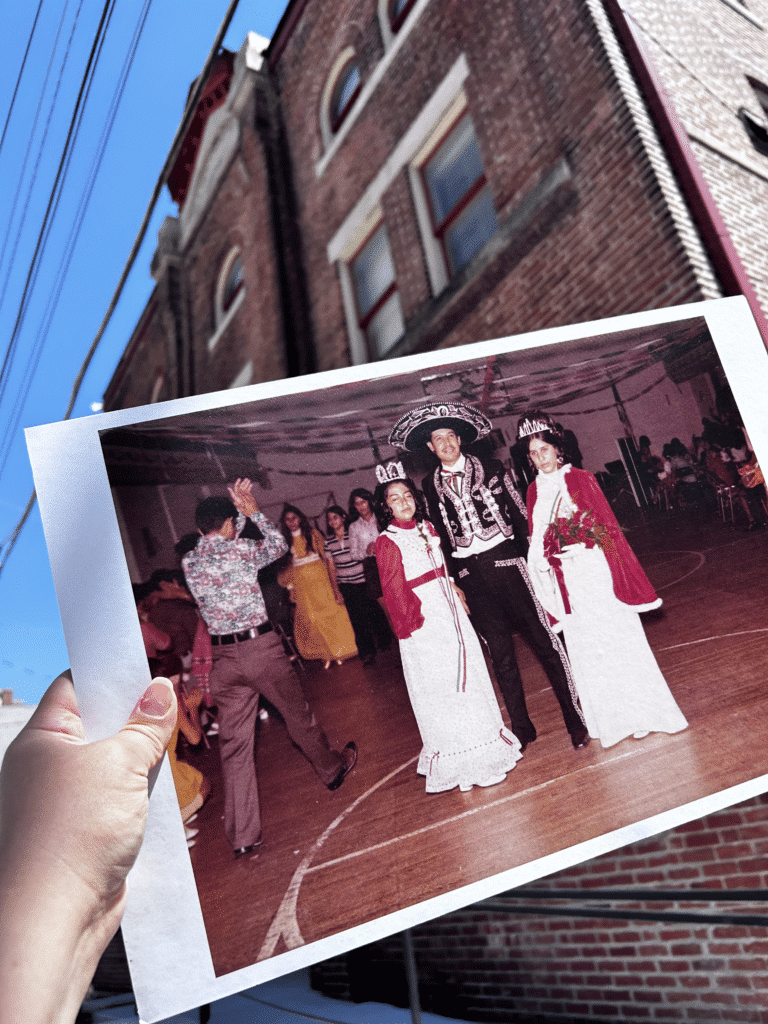

Historian Nicole Martinez-LeGrand holds up a historic photo of a Mexican-American celebration in front of a building that used to serve as the Hispano-American Multi-Service Center near downtown Indianapolis. (Photo courtesy Nicole Martinez LeGrand)

The principal lead of an Indianapolis 1990s oral history project and his subsequent book wrote that the Hispanic community in Indianapolis was “an emerging community.” This didn’t sound right to me. This comment of “emerging” felt incorrect. In fact, I knew it was.

But I haven’t always listened to my own instincts. As a child, when I was asked about my family’s history in the state, I felt dumb and didn’t know what to say. I accepted the absence of Latinos in Indiana as fact and thought my own family may be an anomaly. But it wasn’t true. This is why representation matters in the field of public history and in cultural institutions.

Through time, as a Latino historian, I have learned to use my own identity as a lens that has helped me to uncover these early deprioritized narratives and correct the stereotypes of early Latinos in Indiana.

Soon, Nicole found more definitive proof of substantial Latino presence in Indianapolis much earlier than the official historical narrative had indicated. She conducted oral history interviews with the children of the now-deceased Feliciano and Maria Espinoza, who owned a Mexican grocery store called “El Nopal Mexican Market” that was bulldozed when Interstate 65 was built. Where there’s a grocery store, there is a neighborhood, Nicole learned. The Espinozas’ story was the evidence that Nicole needed to follow the trail and more fully uncover the history of Latinos in Indianapolis history, including “El Barrio.”

Because of her determination and her close ties with the Latino communities she documents, Nicole has become the go-to source for Latino history in Indiana, publishing her findings in a ground-breaking book in 2022: Hoosier Latinos: A Century of Struggle, Service, and Success. Inspired by the energy created by HLI’s activation, she is now leading a project to create a short video documentary of El Barrio, with testimony from some of the surviving residents. She has since talked to them about the activation performed by HLI 2024.

Felix Espinoza works at the family’s business, El Nopal Mexican Market, 1960s

(Photo courtesy Indiana Historical Society)

After sharing this activation experience with a few former residents of the neighborhood, they shared that they never fully realized the history of the neighborhood and its cultural impact on the city. They were surprised that history practitioners from around the country would be excited by this history as well. I imagine they shared a similar feeling I had growing up – that our history is not that important in the larger story of Indiana.

I think my work over the years has restored pride in many who never saw themselves in history. I hope my efforts inspire future historians and museum practitioners from all backgrounds to dig a little deeper or to join the ranks of exploring underreported communities in their own cities. Thanks to the 2024 HLI cohort, I know that I am not the first person to do this work and know that I will not be the last.

Nicole’s work demonstrates the importance of bringing more perspectives into our field and into leadership positions. If you are one of those emerging leaders with the same desire to use your unique voice to enrich our field, please apply to become part of HLI’s 2025 cohort. Your perspective is important.

HLI Applications are due January 15, 2025

HLI Applications are due January 15, 2025

The program meets in Minneapolis from June 16 – 27 and then with periodic virtual meetings for 3 months.

Six scholarships are available.

Andrea Jones (she/her) is both the Director of the History Leadership Institute and an Washington DC-based independent consultant. She helps museums to create transformative learning experiences and to develop values-driven leaders. You can find her at PeakExperienceLab.com

Follow her museum thoughts on LinkedIn, Facebook, and occasionally TikTok.

Resources: