National Narratives

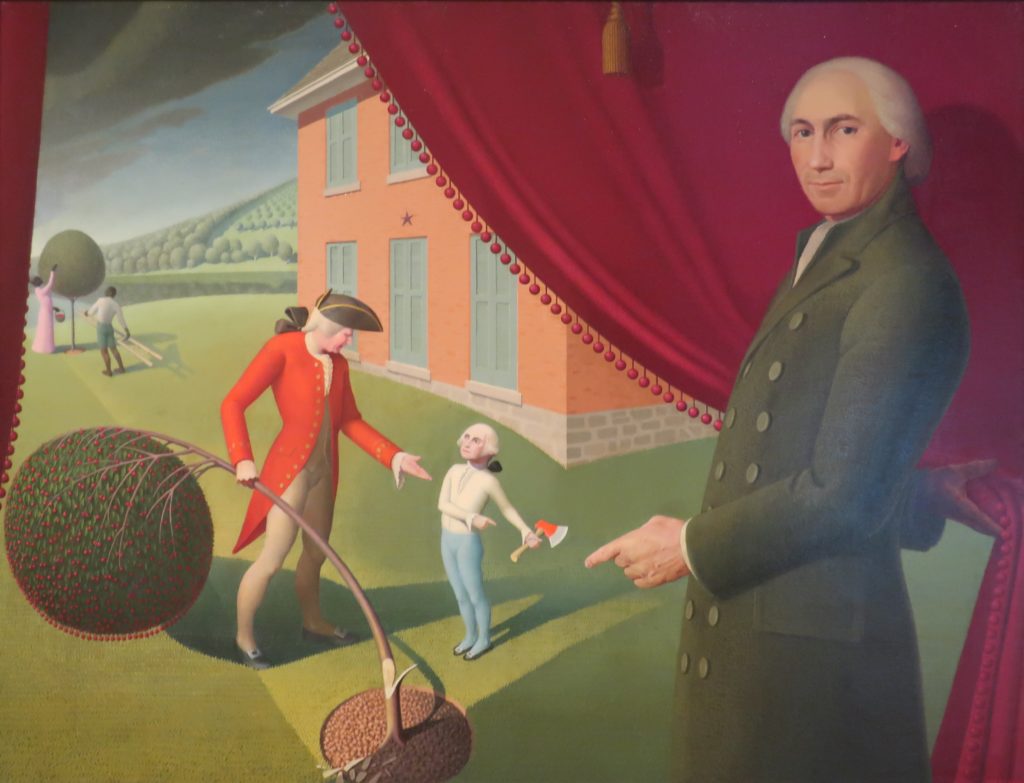

I have lately been thinking about national narratives and their importance. National narratives give us a sense of purpose and unite us as we work together to reach common goals. But because such narratives are aspirational, they also easily spill into the realm of myth, which then creates problems in how we are supposed to interpret and learn from them.

Lately we are engaged in reevaluating our national narrative, which creates anxiety about who we are and what we are trying to accomplish as a country. In many ways, though, we as Americans are constantly engaged in reevaluating our national narrative. It’s one of our defining traits. Perhaps it is because we are still young in comparison to other “Old World” countries—although from an indigenous perspective, we are as old as anyone else. Perhaps it is because we were founded as a democratic nation, which creates an ever-shifting sense of perspective about who we are. Or perhaps it is because we are a land of immigrants, so we need to incorporate the new ideas and traditions that they bring with them into our own.

With these reflections in mind, I picked up These Truths: A History of the United States by Jill Lepore. She is one of the first historians in a while to tackle writing a national narrative for the U.S., and I was curious to see how this Harvard professor approached such a daunting task in our politically fraught times. The bookstore where I purchased her book also carried a new translation of The Aeneid by Vergil that I had been looking for, the latest in what seems like a recent series of classic works to be translated into English for the first time by women, so I bought that as well. (By the way, the perspective that women bring to these translations does make a difference, and I find the clarity of their prose to be a revelation.)

But what I did not realize until I returned home with the two books and compared them side-by-side is that they are both national narratives. Even more, Shadi Bartsch, the translator of The Aeneid, argues in her introduction that embedded in Vergil’s epic is a critique of such narratives as national myths. How does such a critique play out in both works?

When Vergil started writing, he was presumed to have set out to create a Roman epic that would both honor the emperor Augustus by tying his consolidation of the Roman Empire to an ancient past and sit alongside Homer’s Greek epics, The Iliad and The Odyssey (which, by the way, were written six to seven hundred years earlier). For his epic, Vergil uses the Trojan War from Homer’s works as context, but he connects Rome’s destiny to the fate of the Trojan warrior, Aeneas, who after losing the war must take his people on a quest to found what will eventually become a great empire.

Sounds great, except Vergil populates his text with elements of confusion and self-contradiction that end up complicating its status as a national narrative or myth. Aeneas is a problematic hero. We rarely see him act heroically, even though the text constantly refers to him in heroic terms. He lies, to the point where we question whether to believe any of the stories that he tells about himself. And the epic passes over what is clear in other ancient sources in which he appears: that Aeneas is a traitor. What Vergil seems to be arguing, Bartsch maintains, is that creating a collective memory in the form of a national narrative necessarily involves a collective forgetting (which leads us, by the way, back into the realm of myth).

But what happens when we start to remember—and what we remember starts chipping away at the foundation of what we thought was our collective memory? In some ways, Lepore’s approach to presenting our national narrative falls in line with Vergil. She points out the contradictions that are embodied in the three truths that sit at the foundation of our country: political equality, natural rights, and the sovereignty of the people. All three become problematic once we start examining them from the perspective of various people with different needs and histories—not to mention that action adhering to one truth can oftentimes violate the sanctity of another—which is why the designers of our government created a balanced system of competing branches and political forces.

National narratives are complicated. Do we want history (as an act of remembering) or do we want myth (as an act of forgetting)? If we want history, we have to accept the contradictions that necessarily come with it, and if we can’t accept this condition, then we run the risk of losing any chance at a cohesive identity by means of a national narrative. And if we want myth, then we have to be comfortable with the forgetting and potential lies that come with it, and if we aren’t comfortable with misinformation, then we run the risk of memory, truth, and history popping up at any time to reveal how flimsy our social cohesion really is.

–Anthony Vaver, Local History Librarian

Recommended Reading:

- These Truths: A History of the United States, by Jill Lepore.

- The Aeneid, by Vergil, translated by Shadi Bartsch.

- The Aeneid, by Vergil, translated by Sarah Ruden.

- The Odyssey, by Homer, translated by Emily Wilson.

- The Iliad, by Homer, translated by Caroline Alexander.

- An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz.

- A Black Women’s History of the United States, by Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross.

* * *

New Exhibit!

New Exhibit!

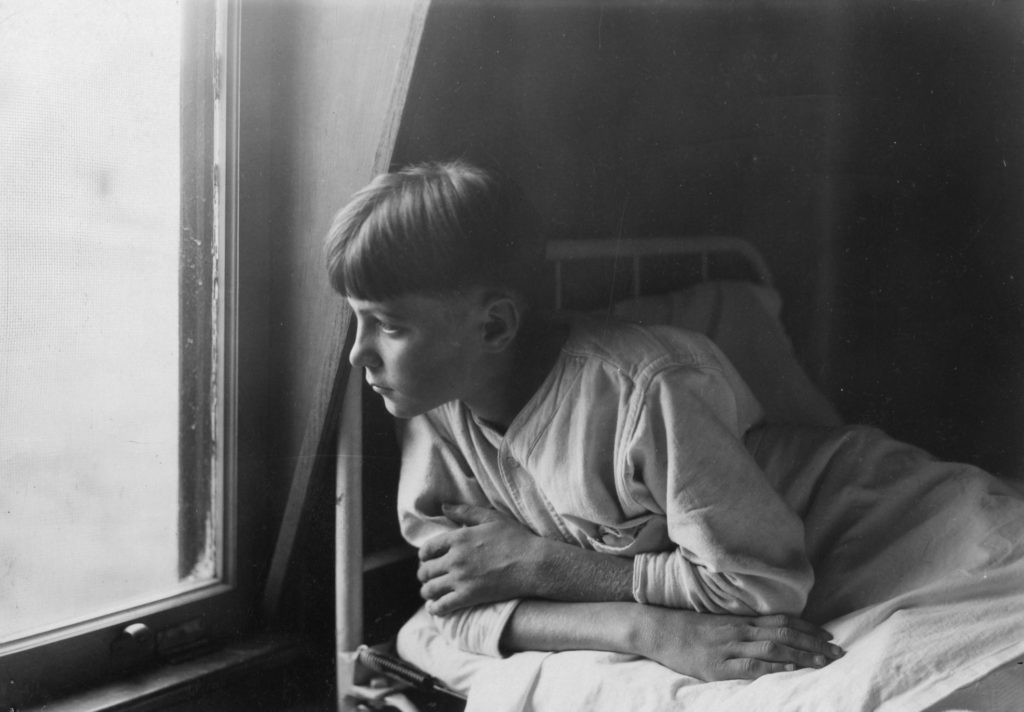

The Westborough Center’s newest exhibit, “Changing Pictures of Childhood: A Comparative History of Child Welfare in Westborough” is now on display in the Westborough Public Library through the end of September.

The exhibit compares two different approaches towards address the needs of children facing social challenges that were practiced in Westborough at different times. Pauper apprenticeship—where poor children were bound by contract to work as a servant in another family’s home—was used in Westborough during the colonial period and the early years of the United States. Westborough was also the site of the first publicly financed reform school for boys, which later became known as the Lyman School for Boys. Photographs taken during the years 1905-1912 illustrate the lives of the boys during this time, roughly one hundred years after pauper apprenticeship was the norm. By comparing these two approaches towards child welfare, we gain a window into how conceptions of childhood itself changed historically over this period of time.

The exhibit begins in the main room of the library on the first floor (over the computers) and continues into the Westborough Center. The exhibit is also enhanced by an online version. And don’t forget to take a look at the display case outside the Westborough Center, which contains a couple “exhibit extras.”

* * *

Did you enjoy reading this Westborough Local History Pastimes newsletter? Then subscribe by e-mail and have the newsletter and other notices from the Westborough Center for History and Culture at the Westborough Public Library delivered directly to your e-mail inbox: https://www.westboroughcenter.org/subscribe-to-updates/.